Can we call quinoa a grain? Why do people care? Where did all these geese feet come from, and what does Ban Ki-moon have to do with it? On long winter runs, Katherine’s mind wanders over such questions.

In the final two months of 2012, questions about quinoa and its status as a “grain” came up three separate times within my earshot. This was odd in itself, but it launched a cascade of coincidences. On a run near the baylands, my mind was idling back over those conversations, when I noticed for the first time a little weed along the trail, looking much like one of quinoa’s relatives, a saltbush. (The crushed specimen I carried home in my shoe laces keyed out as Atriplex semibaccata, Australian saltbush.) There is also a gorgeous and much larger saltbush species along the trail, and yet another relative, an edible Salicornia species (“sea beans”) that fills the marshy areas next to the bay. Along with quinoa, spinach, beets, and chard, all of these species belong to the (former) goosefoot family – the Chenopodiaceae – which is now considered a branch nested within the Amaranth family. Quinoa is a central member of this old family, belonging in the namesake genus Chenopodium.

Click to enlarge. Relationships among edible species in the Amaranthaceae, part of the order Caryophyllales. Relationships and characters based on Judd et al. (2nd ed) and the Angiosperm Phylogeny Website ver. 12.

Just as I was feeling surrounded by goosefeet on the trail, I ran into a merry band of actual avian Canada geese, who clog up the trail this time of year and leave goose footprints in the mud. This seemed like a convergence worthy of the Mayan calendar (also much discussed in December of 2012), but I dismissed it, since quinoa was domesticated by people who lived much farther south, in the Andean highlands. It all came together that very afternoon, though, when co-author Jeanne reported that the United Nations General Assembly had declared 2013 to be the International Year of Quinoa. Suddenly it made sense that various friends and family would be much more interested in quinoa than the possible end of the world. The UN had planted the seeds of this superfood in their brains.

Is quinoa a grain?

There are at least three solid reasons for asking whether quinoa is a grain: worries about gluten; plans for an alternative pilaf; and genuine interest in what counts as a botanical grain and the seed morphology of quinoa. First, there is no need to worry about gluten in quinoa. As Jeanne has explained elsewhere, troublesome gluten is found only in a single tribe of the grass family, which is very distantly related to the Amaranth family. Of course lacking gluten means that quinoa can’t be ground to make a yeast-leavened bread, but – to answer the second question – it is terrific in a pilaf, salad, or soup. See Michelle’s recipe below for a delicious wintertime version of quinoa salad.

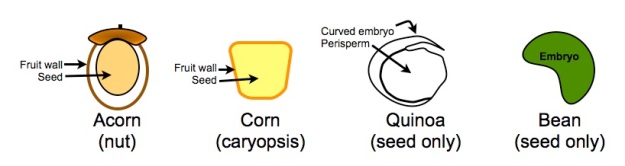

So from a dietary point of view, quinoa is not a “grain” to be avoided, although it functions as a grain in recipes. What do botanists consider to be grains? Even in botany, grain is a very general term for something small and round, such as a pollen or starch grain. What most people mean by a botanical grain – wheat, rice, corn – is a special type of fruit, technically called a caryopsis. Not that botanists go around talking about multi-caryopsis cereal or anything, as tempting as it may be. A caryopsis is a one-seeded fruit whose wall is dry and thin and fused to the seed inside. Usually the entire fruit functions much like a seed would. It is dispersed and planted just as many other seeds would be. As an example, imagine an unpopped kernel of popcorn. It is an entire fruit by itself, although it’s hard to see it as more than a seed. Compare it to a tomato, which is large, fleshy, and contains many obvious and discrete seeds. A caryopsis is similar in some ways to an acorn, which is also a dry, thin-walled fruit containing a single seed. The acorn fruit wall, however, is not fused to the seed inside. In any case, the caryopsis is the fruit type typical of the grass family, and as discussed above, the grass family is only distantly related to the amaranth family.

What is the quinoa pseudograin then?

What we buy in the store is simply the quinoa seed, removed from its fruit. (Yes, the fruit is dry, with thin walls, and contains only a single seed, but it is not fused to that seed, so it is not a caryopsis.) The seeds are usually washed and dried before packaging, to remove bitter saponin, a digestive irritant that deters herbivores. Most recipes nevertheless recommend rinsing the seeds before cooking them.

Whether you rinse or not, it’s instructive to play with the seeds before cooking them. The seed has an interesting shape, much like a slightly flattened cat curled up on a bed. As with many seeds, the bulk of it consists of nutritive tissue that would normally serve to feed the embryo during germination and early seedling growth. In an uncooked seed, that tissue is chalky and opaque looking, but it becomes almost translucent when cooked. In the Amaranth family, the tissue is perisperm, instead of the usual endosperm, and it is derived from the mother plant only, not from both parents. This is not a difference the cook can see or taste, however.

Wrapped around this tissue is the embryo itself, long and very thin and curved. As noted on the phylogenetic tree above, a curved embryo characterizes the core group of the order Caryophyllales. In cooked quinoa, the embryo often escapes its perisperm and little embryos can be seen scattered over other ingredients in the dish. You can distinguish the baby leaves from the root-end of the embryo by pressing gently on it to separate the leaves (cotyledons).

If you save out a pinch of uncooked seeds, you can sprout them and watch the embryo turn green and stretch up towards the light. Simply wet them and spread them out on a wet paper towel in the bottom of a glass dish. Keep them covered loosely for a day or two, but allow them to see the sun once they start to grow. The roots (radicles) will come out first, followed by the shoots, which will green up over a period of days. Some of the seeds will fail to germinate and begin to rot, so it’s good to rinse the seedlings gently with clean water occasionally. Sprouted quinoa can be cooked, and very green sprouts may be eaten like alfalfa sprouts.

Much has been written about quinoa’s history and its high nutritional value, so I won’t take the time to go into those aspects here (see instead here and here). The UN General Assembly has eloquently summarized quinoa’s many merits in its International-Year-of-Quinoa declaration. For our purposes, it’s enough to know that it is delicious, nutritious, versatile, easy to cook, and gluten-free. Perhaps even more importantly, it is very often produced by fair-trade cooperatives of small-scale farmers in Bolivia and Peru. (However, recent articles in Time and The Guardian and another in Mother Jones raised concerns about the social and environmental effects of sudden high demand for the crop). In the US, the only real domestic source is high-elevation farms in Colorado. (Update: see Stephen Gorad’s Quinoa World for more cultivation tips and recipes.)

Where did all these goosefoot species come from?

Why do these goosefoot relatives grow so abundantly in the marshy areas around the San Francisco Bay? For the same reason that the ancestors of our domesticated beets evolved along the shores of the Mediterranean. Many plants in the Amaranth family tolerate dry or very saline conditions remarkably well, and both conditions are common along sea shores and in baylands. For many species in the family, being tolerant of water stress involves being succulent – fleshy and composed of large water-storing cells. Saltbush and beets are not really succulent, but spinach sometimes leans in that direction. And then there is Salicornia, a.k.a. sea beans, saltwort, samphire, or pickleweed. One of several edible Salicornia (Greek: “salt horn”) species fills the low areas by the bay that are routinely flooded with salty water, and it is definitely succulent. The plant looks like a collection of thin, fleshy green fingers, often with red tips. The stem is fleshy and partially enclosed by fleshy leaves that are barely larger than scales. Even the flowers are embedded in the fleshy stems and bracts. Older stems contain a tough central strand of vascular tissue, but younger stems are tender, crunchy, and salty. These are best collected in the summer.

A very nice description, and what looks to be a terrific recipe for sea beans can by found on the site Hunter, Angler, Gardener, Cook.

For now, though, let’s ring in the International Year of Quinoa with a lovely winter salad. Best wishes for a happy and healthy 2013 from the Botanist in the Kitchen.

Quinoa salad with mushrooms, butternut squash and watercress

Here is another salad that is flexible to what you have available. Feel free to use a combination of mushrooms or to change the squash or greens. Just remember, the grains contribute the nuttiness, the squash give the sweet caramelized flavor and the greens the spiciness. Delicata squash and arugula would be great alternatives. If using shiitakes, be sure to stem them.

(Note from KP: For a three-goosefoot version, use spinach for the greens and roasted beets in place of the roasted squash. The spinach will be less spicy than watercress, and the beets less sweet than squash, and the entire dish will have a much earthier flavor.)

Serves 4

1 cup quinoa

1/2 pound maitake, shiitake, or oyster mushrooms, sliced

2 1/2 pound butternut squash, peeled, deseeded, and sliced 1/4 inch

thick

1/2 cup good olive oil

Pinch of chili flakes

1 large shallot, minced (about 3 tablespoons)

Juice of one lemon

2 ounce chunk of Parmesan for shards (cut with a vegetable peeler)

Small handful of mint, chopped

2 large handfuls of watercress (about 2 ounces)

Heat oven to 450° degrees.

Rinse quinoa under cold water to remove the bitter coating. In a medium pot, bring quinoa and 2 cups water to a boil. Cover, reduce heat to low, and simmer until quinoa is tender, about 15 minutes. With a fine mesh strainer, drain any excess water from quinoa. Return drained quinoa to the pot, cover and let rest for another fifteen minutes. Pour quinoa into a large bowl and drizzle two tablespoons of olive oil over it.

In another large bowl, toss squash with 2-3 tablespoons of olive oil, salt and chili flakes. Spread squash out, in a single layer, on two baking sheets and put in oven. After 10 minutes, rotate pans to make sure that squash is roasting evenly. Carefully move any dark pieces to the middle of the pan and any lighter pieces to the edge. Roast for 5-10 more minutes until squash is tender and caramelized. Remove from oven and set aside.

Heat a large sauté pan over medium high heat. When hot, add 2 tablespoons of oil and the mushrooms. Stirring occasionally, sauté mushrooms till golden and caramelized, about 5-6 minutes. Add shallots to the mushrooms and cook for 1-2 more minutes. Add mushroom mix to the bowl of quinoa.

Squeeze juice from 1/2 a lemon over the quinoa, and toss in Parmesan, mint and watercress. Taste salad and adjust with more lemon, oil and salt. Gently fold in squash slices and serve with fresh ground pepper.

Pingback: Nibbles: Potatoes, Quinoa, Biofuels, Raisins

Great post – except I’ve got a half written, half recorded video blog which is eclipsed by this. I had some difficulty finding quinoa to celebrate the year 2013 in the UK until I discovered it in one of the largest chains, Tesco, even a quite small one.

LikeLike

Please do finish your video — I’d love to see it, as would other readers. And I’m excited to follow the AoB blog, which I’ve just joined.

LikeLike

The AoB blog is awesome. I’ve added it to our blog list. Great videos, Pat! And thanks so much for your kind comment.

LikeLike

Loved your article, Katherine. I learned a lot. Thank you! I was a founder and first President of Quinoa Corporation, the company that introduced quinoa to the world outside the Andes, back in the early 80’s. The question of whether quinoa is a grain or not was started by one of my partners, Dave Cusack, and sometimes I wish he hadn’t brought it up. It just confuses the ordinary consumer. What I’ve been saying is that although quinoa may not technically be a grain (in that it is not a grass like wheat, rice, millet, barley, etc.), for reasons of practicality, it should be considered a grain. It is harvested like a grain, stored like a grain, transported like a grain, prepared like a grain, and eaten like a grain, and more importantly, it has the potential to be a major basic food commodity for the planet like the other grains. Oh, and one thing about quinoa sprouts. Usually when people do sprouting at home, once the sprout has reached the optimum length, they put it in the refrigerator to stop the growth. Doing so with quinoa will NOT stop its growth. It just keeps growing and growing. Quite an amazing little seed, or grain, or whatever it is, no? 😉

LikeLike

Thank you, Stephen, for your kind words and especially for introducing quinoa to the world. As a vegetarian whose diet was shaped in the late 80’s, I doubt I’d have been as successful or happy without it! The post was inspired partly by the weirdness of hearing friends ponder the grain question so earnestly and partly by the opportunity to talk about seed and caryopsis anatomy. I’ve just added a new link in the text to Food Tank’s article on quinoa. You might be interested: http://foodtank.org/news/quinoa-key-to-global-food-security

LikeLike

Pingback: Welcome to 2013, the International Year of Quinoa | Landwirtschaft aktuell

The cascade of coincidences doesen’t stop: as I finished reading this article I entered the kitchen and my housemates were talking about quinoa!

Congratulations for the blog, for what mine are worth!

LikeLike

Too funny. And have you seen all the recent articles following up on the Guardian article? Quinoa has suddenly become controversial.

I hope you had lots to tell your housemates! Thanks for your congrats and thanks for reading.

LikeLike

I guess I should put my two cents in about the Guardian article, and the previous articles it was based on. I really hate to see articles like these pushing a story that there is a problem with buying and eating quinoa from Bolivia. It discourages a lot of well meaning people from doing something that it both good for them, and good for people in Bolivia. The fact of the matter is that these articles just aren’t true. Indeed, the opposite is true. The trade happening with quinoa has been bringing much needed wealth to countries (particularly Bolivia) that desperately need it, and when I say “desperately” I mean it. These are some of the poorest countries on the planet. There is more than enough quinoa grown there to feed their own people and to export. In any given crop, there is plenty of quinoa that is not up to par for export. It is still nutritionally excellent, only it doesn’t look quite as good. And did you know that most of the quinoa that leaves Bolivia does NOT go to the United States or Europe. It is smuggled over the borders to feed local demand in Peru. There is a lot going on that people just are not aware of. Are there problems? Of course, but they are not what is being put forth in this story. Articles like these are just too simplistic. They rely on what someone else said awhile back, not on first hand investigation. Please see: http://bearwitnesspictures.blogspot.com/2012/11/an-open-letter-to-npr-regarding-quinoa.html

LikeLike

Thank you Steven for the response and the link. I do not feel that I can weigh in on this issue without better firsthand knowledge, but I very much appreciate readers helping others to follow the discussion on their own. The Mother Jones article is another thoughtful resource which contains additional useful links.

Katherine

LikeLike

Pingback: Greens: why we eat the leaves that we do | The Botanist in the Kitchen

Hi there to all, the contents present at

this website are actually amazing for people experience, well, keep up the

nice work fellows.

LikeLike

Quinoa can be eaten as greens and the flavor is like hazelnuts and spinach. I think that quinoa greens are way tastier than spinach or chard and the superior nutrition is similar with greens as the grains (crazy high protein). Amaranth too can be eaten as greens but not salad, they make a great pot herb. Oh and btw, this stuff is so easy to grow their is no need to argue about importing it from Bolivia or Peru because you can grow it yourself or ask your friendly local farmer to grow it for you. If you are in Bay area I can grow some for you. Thanks for a very informative article!

LikeLike

Thanks, Trevor. I have sprouted the seeds for class to illustrate their long cotyledons, but your comment makes me think I should keep them growing. I think I’ll try it.

LikeLike

Pingback: Alliums, Brimstone Tart, and the raison d’etre of spices | The Botanist in the Kitchen

Pingback: Sugar | The Botanist in the Kitchen

Pingback: Closing out the International Year of Pulses with Wishes for Whirled Peas (and a tour of edible legume diversity) | The Botanist in the Kitchen

Pingback: Maca: A Valentine’s Day Call for Comparative Biology | The Botanist in the Kitchen

Pingback: The Botanist Stuck in the Kitchen, rummaging for beets | The Botanist in the Kitchen

Pingback: The Botanist in the Root Cellar | The Botanist in the Kitchen