Inspired by spring and the appearance of both artichokes and asparagus, Katherine explains artichoke morphology in the first of two posts about bracts and scales.

Artichokes don’t exactly look like food, and their name in English is homely and offputting. The scientific name is no better. Cynara cardunculus variety scolymus rolls off the tongue like a giant ball of tough spiny bracts. I’m not ready to call it an onomatopoeia, even though artichokes are giant balls of tough spiny bracts. And the word “bract,” on its own, is just flat-out ugly. But artichoke bracts have delicious meaty bases, and they protect the tender inner part of the bud which we call the heart, so I am a C. cardunculus var. scolymus bract fan.

Bracts are basically leaves that have been modified in some way, often made tougher, sometimes thicker, occasionally thinner and colorful. They subtend (stick out below) a flower or cluster of flowers. In most species they quietly and dutifully protect flower buds, but sometimes they join the flowers as part of the overall display. The hot pink parts of bougainvillea “flowers” and the bright red “petals” of poinsettias are showy bracts. Artichokes have two kinds of bracts: involucral bracts (also known as phyllaries) are the giant green scales making up the bulk of the artichoke; receptacular bracts, or chaff, are tiny, but they contribute to the irritating character of the choke. We delve into more bract details in the section on artichoke evolution.

What is an artichoke?

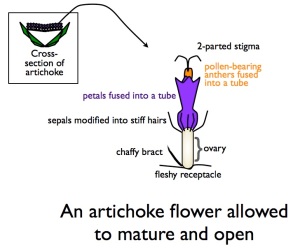

Artichokes are in the sunflower family, the Asteraceae, along with dandelions and daisies and lettuce and chicories and thistles and all the other composites. The edible part of an artichoke is a gigantic “flower” bud that develops on a large spiny Mediterranean thistle. I qualify “flower” because the bud contains more than just a single flower. If allowed to live out its natural life, the bud would open to reveal hundreds and hundreds of tiny long and thin rose-lavender colored tubular flowers. Some nice images can be found here and here. All of those flowers are clustered into a flat-topped composite head where together they mount an awesome display that attracts bees collecting both nectar and pollen. Numerous ecological studies on many different species have shown that extra-large floral displays generally attract more pollinators than small ones do. Some flowering plant species make single large and showy flowers, but many many species group their smaller flowers into inflorescences. Inflorescences in the Asteraceae are particularly well-organized, and some members of the family go so far as to mimic single large flowers. For example, the heads of sunflowers and daisies have an outer ring of flowers with extra-long tongue-shaped tubes of petals that look very much like the whorl of petals around a single flower. The rest of the head is covered with short-petaled flowers that function primarily in reproduction. By contrast, artichokes and other thistles have one kind of flower throughout the head, and all flowers serve to attract and reproduce. In the Asteraceae, the head is properly called a capitulum.

The sunflower family is one of the largest families of flowering plants, with over 20,000 species. Within the family, artichokes are closely related to cardoons – actually varieties of the same species – although cardoons are cultivated for their “edible” leaf midribs. (Anyone interested in cooking cardoons should consult Deborah Madison’s excellent new cookbook, Vegetable Literacy. It makes me perversely happy that she seems as skeptical as I am that cardoons are worth the trouble to prepare.)

How to make an artichoke if you are Evolution

One way to understand the structure of an artichoke is to imagine how it evolved from simpler and more familiar structures – specifically, the kind of inflorescences found in the families most closely related to the sunflower family. The likely evolutionary transitions have recently been described by Pozner et al., based on careful observation of developmental morphology. Their paper includes some very useful diagrams, and interested readers with academic library access should definitely track down a copy using the link below* . My description here is more conceptual and omits some details but is essentially what they report.

If you were Evolution setting out to make a composite head, you would start with the raw ingredients available to you, which would include a flower-covered stalk, or an inflorescence. Imagine that it is the kind of inflorescence found on some orchids (the kind a co-worker gives you for your birthday) or a larkspur or even a weedy mustard plant. On these inflorescences, the oldest flowers are at the bottom, and new flowers continue to develop at the top. The flowers are arranged around the stem like steps in a spiral staircase, and each flower is subtended by a small leaf or bract.

Now, if your flowering stalk has any little side branches with flowers, get rid of them. Next, take Evolution’s handy opposable thumb and forefinger and grasp the stalk just under the lowermost flower. Push all the flowers up towards the top of the stem so that they are clustered closely together. Thicken up the flower-covered part of the stem so that it is fleshy, widest at the bottom, and tapering towards the top. You now have a fat cone covered in flowers, which may even look a bit like the center of a black-eyed Susan. Keep expanding the lower part of the cone so that the inflorescence becomes wider and flatter and finally takes on the shape of a shallow dish. We can now call the “dish” what it is: a receptacle. The receptacle, along with a very thick stem, provides mechanical support for the inflorescence, serves as a site for nutrient storage and transfer, and will also eventually be delicious for humans to eat with butter. Thanks, Evolution.

But all of those tiny flowers will need to be protected from bumps, desiccation, and hungry animals until they are ready to open, and bracts are the perfect solution. As explained above, artichoke bracts are modified leaves, made tough and thick and tipped with a sharp curved spine. As Evolution, you will want to surround the receptacle and its flowers with several rows of tightly overlapping bracts, which botanists will call an involucre (“IN-VO-luker”). The bracts will stay closed around the receptacle until the flowers are ready to be presented to pollinators. When they spread to allow the flowers to appear, they will still serve as a defense against herbivores. Because the bracts are derived from leaves, they are arranged on the stem in a Fibonacci spiral * , and this pattern becomes even more apparent when they are closely packed at the top of the stem.

Stiff hairy pappus, which replaces the sepals in a composite flower. The pappus becomes a parachute that helps disperse the fruit.

If the center of the artichoke – the choke part – is nothing but flower buds, it shouldn’t be irritating, and yet it is. A second set of bracts, the receptacular (chaffy) bracts, are partly to blame. Recall that flowers on an inflorescence are generally associated with bracts, and artichoke flowers follow this rule as well. Their bracts are small but particularly stiff and bristly. The flower buds themselves are also part of the problem. The petals of the flowers are soft, but the sepals have been modified into a collection of long gag-inducing hairs called a pappus. Thanks, Evolution. This pappus is easy to see on a puffy white mature dandelion head. Long after the petals have fallen, the pappus remains attached to the ovary and serves as a parachute to carry the fruit long distances through the air.

How to make an artichoke if you are in the kitchen

Another way to understand the structure of an artichoke is to prepare, cook, and eat one. There are more elaborate ways to cook an artichoke, but here I’ll simply describe how to clean and boil one.

1. Examine the whole artichoke and notice that the involucral bracts are arranged in a spiral around it. Carefully note the sharp spines at the tips of each bract.

2. Lick your fingers to taste the bitter compound cynarin. The bitterness will stay on your hands, knife, and cutting board, so be sure to wash all of these before preparing other food.

3. Cut the stem from the bottom of the artichoke to make a nice flat base. Notice the pithy inner core surrounded by a ring of tissue containing many vascular bundles that feed the bracts and flowers.

4. Remove some of the smaller lower bracts, which are not as closely associated with the receptacle and don’t have as much delicious tissue at the base.

5. Use scissors or a knife to trim the spines from the tops of the bracts. Notice how tough the bracts are.

6. Saw the upper third from the top of the artichoke. Doing so gives you a good view of the spiraled layers of the inner bracts.

None other than the California Artichoke Advisory Board erroneously calls the bracts “petals.” Although the inner bracts may look like the unfurling petals of a rose, this is an alarming mistake. I would not take advice from this organization on anything.

7. Gently spread the bracts under running water to flush out any hidden creatures or their frass (poop). If you find frass, look carefully for the source in case it has not abandoned your artichoke.

8. Place the artichoke in a steamer basket over simmering water for about 40 minutes, until the bracts are soft and pull easily away from the receptacle.

9. Eat the artichoke by pulling off the bracts, dipping their fleshy bases into browned sage butter or salted oil or aioli, and pulling the dipped flesh through your teeth.

Although artichokes are notoriously ill-suited to wine, many experts recommend pairing them with an acidic dry white. I like to sip on Navarro gewürztraminer because of its distinct citrus notes.

10. Once you get down to the smallest inner bracts, they may come off in a cone. Dip the base of the cone and eat this.

11. Examine the choke. Run your finger over the hairs to appreciate why you wouldn’t want to eat them. Remove the choke by drawing a table knife gently across the choke. This will pull the flower buds and receptacular bracts away from the receptacle leaving (in spots) the impressions left behind by the ovaries. Notice that the ovary scars form a Fibonacci spiral just as the bracts did.

12. Trim any dark green, potentially bitter tissue away from the bottom of the artichoke and you will be left with only the receptacle. Drag this through your butter, oil, or aioli, and enjoy the best part of the artichoke.

References

Pozner, Zanotti, and Johnson (2012) Evolutionary origin of the Asteraceae capitulum: Insights from Calyceraceae. American Journal of Botany 99:1-13.

http://www.amjbot.org/content/99/1/1.full

From the abstract: “Conclusions: Widely understood as a condensed raceme, the Asteraceae capitulum is the evolutionary result of a very reduced, condensed thyrsoid. Starting from that point, evolution worked separately only on the racemose developmental control/pattern within Asteraceae and mainly on the cymose developmental control/pattern within Calyceraceae, producing head-like inflorescences in both groups but with very different diversification potential. We also discuss possible remnants of the ancestral cephalioid structure in some Asteraceae.” Back

The fabulous Vi Hart explains the Fibonacci spiral http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ahXIMUkSXX0 Back

“Bract” is flat-out ugly? I love the sound of it, and the look of it on things like Euphorbia pulcherrima.

LikeLike

Well they can look pretty, but I guess to my ears “bract” sounds like a bird cackle. To each his own. I was unable to work into the post one of my favorite words, which describes the way stamens are arranged in composites: syngenesious. Now *that* is a mellifluous word.

Thanks for reading!

LikeLike

I love the fact that mellifluous is itself mellifluous.

LikeLike

Pingback: Nibbles: Artichokes and bracts, Colour, DsG and experts, Fish, Genetics, Horseradish, Improved nutrition, Kenyan sorghum, PLant Press

Pingback: Preparing asparagus: the facts about bracts, part 2 | The Botanist in the Kitchen

Thank you for this – it’s informative. I like artichoke hearts because they’re delicious when somebody else has cooked and prepared them, but otherwise, I don’t grow artichokes any more. Disability robbed me of the manual dexterity to pull and dip artichoke bracts.

LikeLike

Pingback: Bamboo shoots: the facts about bracts, part 3 | The Botanist in the Kitchen

Pingback: Going bananas | The Botanist in the Kitchen

Pingback: Leontodon hispidus | Find Me A Cure

Pingback: Helminthia echioides | Find Me A Cure

Pingback: The History of Artichokes – The Plate: Rebecca Rupp

I was researching artichokes for my gardening blog and discovered The Botanist in the Kitchen. What a delightful combination of culinary expertise, scientific fact, and the stuff of nature that always amazes me!

LikeLike

Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: A holiday pineapple for the table | The Botanist in the Kitchen

Pingback: The Botanist Stuck in the Kitchen, Saturday night artichoke edition | The Botanist in the Kitchen