If artichokes are big balls of spiny bracts, then asparagus spears are telescoped rods with membranous scales. In this follow up post, Katherine takes on asparagus, both the tender and the tough, and explains why peeling can’t rescue a woody spear.

Asparagus is a hopeful spring vegetable. Asparagus aspires, breathes in the warming spring air, and optimistically pokes its nose up from the ground. Its tips are clusters of tiny developing branches, still packed tightly like an unexpanded telescope, containing all the potential of a season’s worth of growth. Except that we whack them and eat them before they can realize their audacious plant dreams. There’s no need to feel entirely bad about this, though. The spears stay alive for a while, stubbornly growing tougher until they are cooked or digested.

Preparing asparagus

Preparing asparagus always raises questions. What’s the difference between thick and thin spears? Should the triangular leaves be removed? And should the whole thing be peeled? Much has been written about spear size, so I’ll just say briefly that spears come up from the ground as thick or thin as they are going to be. They do not grow thicker as the spears age; they grow thicker as the perennial underground parts grow. Basically, the thicker and more robust the underground stem is over the winter, the thicker the crop of upright stems will be in the spring.

As for the little triangular leaves, I always pare them away, even though nobody else I know does this voluntarily. They bug me, so I do it. Many chefs recommend peeling the entire stalk, especially when the spears are fat. (If you look at Mark Bittman’s helpful recommendations ignore the inaccurate part where he calls the tip a flower bud. More on that particular tip later.)

If your spears are stringy, the skin is not the problem

While it is true that a chef can eliminate some toughness by peeling an asparagus spear, the skin is only a small part of the problem. That’s because asparagus is a monocot – it belongs to the same phylogenetic group as lilies, grasses, bananas, onions, and orchids. One diagnostic feature of this group is the arrangement of its vascular bundles, or veins. They are scattered throughout the stem instead of being arranged in a ring just under the skin. This is very easy to see in an asparagus spear whose end has dried out.

The veins stay stiff while the rest of the tissue shrinks back, leaving the tips of the bundles poking out a little bit. The same thing happens to corn cobs and the stem end of a banana.

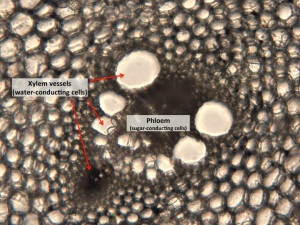

Those vascular bundles contain both soft living cells (the sugar-conducting phloem) and cells with thick stiff walls (the water conducting xylem vessels).

When a spear is very young, the vessels are not numerous and their walls are not very thick, but during normal development the vessel walls accumulate more and more tough lignin. Lignin is a major component of wood, and we cannot digest it. Chewing it is not so easy either. Asparagus strands stuck in your teeth are not dignified, only lignified. The thickness of the xylem walls and their lignin content is greatest at the base of the spear, so it is worth snapping the ends of the asparagus off and using them to make stock for asparagus soup or risotto.

Just under the delicate skin of the asparagus spear there is a layer of thick-walled cells called sclerenchyma, and these also multiply and take on lignin over time. Peeling the asparagus does remove this layer and may reduce toughness a bit, even if the stringy vascular bundles are left behind. The sclerenchyma sheath is there to support the much taller and more top-heavy shoot that our optimistic little spear was hoping to grow up to be.

Another challenge for us in the kitchen is that these stubborn asparagus stems don’t stop developing after they are cut. The enzymes that turn sugar into carbon-rich lignin keep working, and tender spears straight from your local farmer can turn tough if you wait too long to kill them. As it turns out, you can dramatically reduce the activity of these enzymes by putting spears in the refrigerator (Zurera et al. 2000) or depriving them of oxygen (Waldron and Selvendran 1990). Refrigeration seems to work well enough that there’s no need to buy a fancy vacuum pump just to keep your asparagus fresh at home. It is important, though, to avoid buying asparagus that may have been on display for several days and not kept cold.

The parts of an asparagus spear

Like many domesticated edible plants, asparagus spears can be hard to map onto our idea of what a plant looks like. The spears are essentially stems whose leaves have been reduced to small scales by evolution and whose branches and flowers have been arrested by an early harvest.

In the post on artichokes, I described bracts as leaves that had been reduced in size, thickened, colored, or otherwise modified for another function. Bracts, however, are associated specifically with flowers or flowering branches and not with regular vegetative branches. The tip of the asparagus is not a set of flower buds; consequently the thin little triangular leaves of asparagus are not bracts, but rather “scale leaves” that protect developing branch buds. The tip of a growing asparagus spear is the part of the stem that will become branchy (if it is not harvested). All those immature branches subtended by scale leaves are bunched together at the top like a new telescope, waiting to be extended. I do not know whether all of the branches are in place at this stage, ready to spring forth, or whether still more nodes would be produced. Maybe someone out there knows?

Lacking proper photosynthetic leaves, asparagus makes sugar with its stems. In some species (e.g., asparagus ferns, which are not ferns but are asparagus), the stems have become flattened and look like leaves. Leaf-like stems in general are called cladodes. It was recently shown by Nakayama et al. (2012) that the African asparagus fern pulls off this trick by expressing leaf-identity genes in its stems that give them a top and a bottom side. Garden asparagus (A. officinalis) has very thin cylindrical cladodes that look less leafy, although they are often described as fern-like (meaning leafy). They also express leaf genes, but instead of gaining a top and a bottom side, the spatial pattern of gene activity makes them “bottom” all the way around and thus cylindrical.

You can see immature cladodes in your kitchen among the closely spaced scales at the tip of an asparagus spear. The leaf scales that make up the lowermost part of the fat tip only partially hide what would become a large and very feathery branched structure. Those branches would eventually bear flowers, but because garden asparagus is dioecious, they would be either pollen-bearing (“male”) or fruit-bearing (“female”) flowers.

Illustration of garden asparagus. From Wikicommons; image is in the public domain.

Sweet pee and 23 and me

Although I’m taking us out of the kitchen here, it’s hard to resist mentioning what asparagus does to the smell of your pee. A byproduct of asparagus digestion is methanethiol, a sulfurous gas. Some people like the smell, some hate it, and some claim not to smell it at all. A few years ago, some geneticists at 23andMe, a personalized genomics company, looked for a genetic signal of asparagus anosmia, or the inability to smell the methanethiol in pee. The researchers found a variable region of DNA on human chromosome 1 that contains several genes for olfactory receptors and is significantly associated with the ability to smell asparagus pee.

In the end, I have to think that this lingering essence of asparagus is yet another example of its tenacious spirit. Hope springs eternal. And like every tender hope, it takes a tough core to make it stand up.

References

UPDATE: New York Times writer Elaine Sciolino just published a piece on white asparagus and the French who love it. I did not talk about white asparagus here because it is not popular. Indeed, I see it most often in Paris where it has (oddly) been some of the toughest, least edible asparagus I have ever had. I’m normally there in July or August, though, when it is not in season and probably coming from a long distance. On the other hand, the thinner-than-a-pencil green spears found in most Paris markets in the summer are amazing.

Eriksson et al. (2010) Web-Based, Participant-Driven Studies Yield Novel Genetic Associations for Common Traits. PLoS Genet 6(6): e1000993. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000993

Nakayama, Yamaguchi, and Tsukaya (2012) Acquisition and Diversification of Cladodes: Leaf-Like Organs in the Genus Asparagus. Plant Cell 24(3): 929–940. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.092924

Waldron and Selvendran (1990) Effects of maturation and storage on asparagus cell-wall composition. Physiologia Plantarum 80: 576-583.

Zurera et al. (2000) Cytological and compositional evaluation of white asparagus spears as a function of variety, thickness, portion and storage conditions. J. Science Food Agriculture 80: 335-340.

I’m studying horticulture and these posts are brilliant at converting classroom study into relatable kitchen experience. I look forward to receiving your Botanist In The Kitchen emails – keep up the good work!

LikeLike

Thanks, Di. Good luck with your studies, and please feel free to add your observations from the horticultural point of view.

LikeLike

Katherine, you are just wonderful!!!! Hope springs!

LikeLike

Katherine is wonderful. Thanks for reading, Pam!

LikeLike

Hi

LikeLike

Thanks, Pam! You might be the first to get the spring = pee joke.

LikeLike

LOVED this article. A hardy little fellow indeed. Always did wonder what was the reason for the immediate odor one’s pee acquired upon consuming asparagus. I feel so enlightened! So glad you started writing for the common folk

Sue oxox

Sent from my iPad

LikeLike

Pingback: Nibbles: Chickpeas, Cassava, Maize diversity, Potato diversity, Palm display, Global mistrust, Asparagus, Ramps, Local strawberries

Just discovering your blog, and I look forward to reading more.

LikeLike

Wow. Asparagus. Who know they could be so technical? =)

LikeLike

Pingback: Nibbles: Chickpeas, Cassava, Maize diversity, Potato diversity, Palm display, Global mistrust, Asparagus, Ramps, Local strawberries - Agriculture and Aquaculture

Pingback: Crop of the month: Asparagus | Science on the Land

Katherine, this blog is fantastic! I wonder if you would mind me assigning some of your posts (with attribution, of course) as readings for my Plant Bio students.

LikeLike

Thanks, Dana. We’d be delighted for the blog to be used in the classroom. Let us know how it goes!

LikeLike

Yes, absolutely! Please just see the “legal details” bit below for the Creative Commons license. As Jeanne says, we’d love to hear feedback.

LikeLike

Pingback: Bamboo shoots: the facts about bracts, part 3 | The Botanist in the Kitchen

Pingback: Sparanghelul sălbatic | Ierburi Uitate

Pingback: Going bananas | The Botanist in the Kitchen

Pingback: The Extreme Monocots | The Botanist in the Kitchen

Pingback: Eat and Live: How to Hunt Wild Asparagus - The Rainbow Hub

Pingback: Spruce tips | The Botanist in the Kitchen

Pingback: Baking Asparagus and Potatoes Together: A Delicious and Easy Recipe – LittleKitchenBigWorld