Nostalgia emanates from a basket of pears, inspiring Katherine to explain what makes up these glorious, gritty, and gorgeous late-summer fruits.

Last week a dear friend conjured an entire autumn for me when she handed me one of her pears. She had picked it a few days prior from one of the small espaliered trees that guard the outside of her bedroom wall and overlook her garden. It was pale buttery gold with a pink blush, soft and honey-flavored. A month past the solstice, we were still able to enjoy the low sun well into early evening as we sat on her deck and gazed over the garden, savoring the fruit.

Bartlett pears, like my friend’s, ripen in the summer and yet they herald the fall. They appear, and we start the inevitable tumble towards apples, wool socks, and the bittersweet baseball postseason. Other popular varieties, such as Bosc and d’Anjou, tend to arrive later, when we have already come to terms with shorter cooler days.

I love apples, but they are not as emotion-laden for me. Whereas apples seem timeless, even summer pears carry an old fashioned patina. They evoke a time when canning was a skill necessitated by the Depression, but which still made a lot of good sense. My grandmother must have spent a thousand hours canning the soft sweet pears from her trees.

Pears also know how to age right. Apples are harvested ripe from the tree, but pears should be taken when they have reached their full size and before they are ripe. My friend always picks her pears before the squirrels can mark them with bite-sized divots, a practice that also happens to keep them from becoming mealy on the tree. She sent me home that day with a bag of firm green Bartletts and instructions to hold them in a bag in my kitchen for a couple of days. Summer varieties don’t require chilling, but d’Anjou and Comice pears benefit from a month of nearly freezing temperatures, followed by ripening at room temperature (Stebbins et al). The proper aging of pears is all about managing the activity of enzymes that alter various compounds and break down cell walls. Such treatment would ruin high-maintenance peaches, which are horrified by the thought of getting old and don’t take well to chilling.

Pear grit

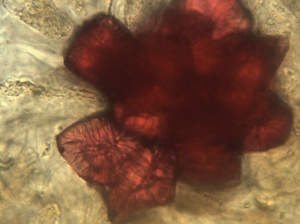

Pear flesh is infused with very fine grit, made of clusters of stone cells. Stone cells, a subtype of sclereid cells, make up some other very hard tissues like peach pits and nut shells. Stone cells are born with their own death as an end goal. They begin as all other plant cells do, with thin primary walls. Then they start to box themselves in. They import the raw ingredients for additional cell wall material through windows that connect them with other cells, and they start covering the inside of their primary wall with secondary wall. They lay down layer after layer, squeezing their living parts into an increasingly tiny area. As they add wall, they keep the window clear so they can keep the supplies coming until the bitter end. Eventually, the window is so deep that it becomes a tunnel, and the entire cell is filled with wall. At this point the cell achieves its final form and dies.

A single gritty bit of pear is usually a cluster of several stone cells, but even individual cells are large enough to discern without magnification. It is possible to stain them so that they show up hot pink under a light microscope, and we sometimes do this in the botany classes I teach. Making stone cells requires both energy and materials, so they probably serve some purpose in the life of a pear. Guarding against herbivores would be a reasonable guess, but I have never found any studies testing this idea. Related quinces also contain stone cells, along with bitingly astringent tannins that most certainly defend the fruits.

Pear shape and structure

Pears have a distinctive enough shape to have inspired their own word: pyriform means pear-shaped and applies to all sorts of animal and plant parts from hairs to throats to rear ends. The common European pear, Pyrus communis, is indeed pear-shaped; the Asian pear, Pyrus pyrifolia, is apple-shaped, or baseball-shaped, or globe-shaped but anyhow not special. Numerous genes contribute to overall shape, but roundness is dominant to pyriform (references in Hancock and Lobos, 2008).

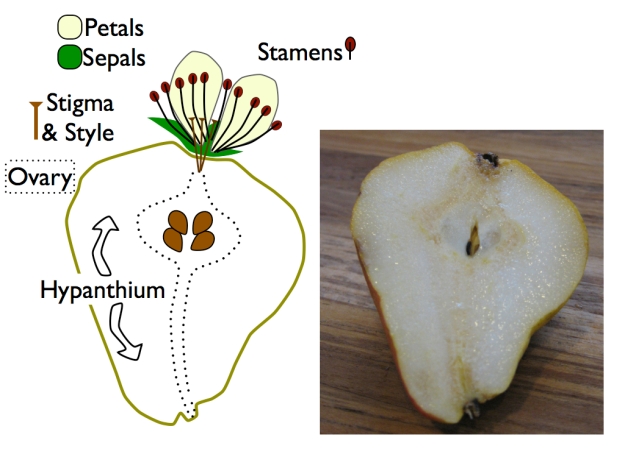

Pear fruit develops from an ovary that is below – or inferior to – the rest of the flower, which is why their stem is on one end of the fruit and the floral remnants are on the other. Viewed from the top, their flowers clearly have five pale petals, surrounded by five green sepals, with a-multiple-of-five number of pollen-bearing stamens towards the inside of the flower. We would normally expect to find the ovary encircled by the stamens in the very center of the flower, but in this case we find only the styles, leading down to the ovary below the point where the distinct flower parts are attached.

The pear fruit comes from an inferior ovary, buried down inside a fleshy hypanthium. Flower parts are drawn larger than scale . Only two petals and three sepals are shown.

I sometimes describe an inferior ovary as being down inside a fancy purse, a protective bag with a drawstring and several rings of frills decorating its top edge. The decoration would be the sepals, petals, and stamens. The styles and their flat stigmatic tops would emerge through the drawn up neck of the bag to receive pollen grains. Much of what we eat would be the bag itself, which is thick and fleshy and fused around the actual ovary. It is called a hypanthium and probably developed (when the flower was just barely a bud) from the same tissue that eventually became the sepals, petals, and stamens. Instead of differentiating into distinct parts, the tissue remained as a mass that grew around the ovary.

The relationship between the flower and fruit is obvious in a pear cut lengthwise. The sepals remain on the fruit, along with some of the stamens and the styles, although the petals fall long before harvest. The bulk of the fruit is the greatly enlarged hypanthium, although the ovary itself also grows to accommodate the seeds inside.

Pears, apples, loquats, and quinces are all pome fruits, a fruit type peculiar to their shared branch of the Rose family tree. They are all derived from inferior ovaries, and their seeds are surrounded by tough papery partitions. The partitions form the core or the star in the center of an apple or pear cut crosswise. Because pomes consist of both the ovary and additional tissue (the hypanthium), they are a type of accessory fruit. Perhaps that’s why a purse comes to mind as I describe these accessorizing fruits.

More so than many other fruits, pears wear personality on their skin. Not only do individual pears have their own charming shapes, each is freckled with lenticels. Lenticels are tiny dots of particularly spongey tissue that allow oxygen and other gases to move through the wax-covered epidermis of the fruit and support the metabolism of the living tissue beneath it. Apples and plums have obvious lenticels, too, yet they never seem to achieve the same hard-earned Tommy Lee Jones look that some pears do.

The art of aging

Back in my kitchen, the hard green pears took only a few days to mellow in the bag. Since then, I’ve been eating them for lunch on fresh spinach with walnuts and a couple of grinds of black pepper. As I sit with my salad in the mellow sun, I try not to panic about my own late-summer birthday bearing down on me. I take a bite of pear and hold it in my mouth and think about my dear friend, my grandmother, my mother, and other women I admire. I vow to follow their examples – becoming softer, yes, but more nuanced, maybe slightly more pyriform, and as full of grit as ever.

Paragon sorbet

Back when my ice cream maker still worked, my husband and I made a pear sorbet and added tarragon on a whim. It was terrific. The basic pear sorbet recipe we used called for making a sugar syrup and cooking the pears in it. Following your own favorite recipe, add a few sprigs of fresh tarragon to your syrup to steep while it cools. Remove the sprigs before you puree the pears, and continue with the recipe. (To learn more about tarragon, see Jeanne’s post.)

Without an ice cream maker, I imagine you could make an amazing frozen cocktail using fresh pear, poire William liqueur, and tarragon. I’m also thinking about adding tarragon to cooked custard to be used in a pear tart or a pear soufflé.

References

Hancock, J.F. and Lobos, G.A. (2008) Pears. In Temperate Fruit Crop Breeding (J.F. Hancock, ed), Springer.

Pear-tarragon martini–the vermouth will add another Artemisia!

LikeLike

Oh, yes!

LikeLike

Oh, man. This is wonderful info and the idea of that cocktail sounds lovely. But, then, my favorite cocktail every involves pear nectar and pear flavored vodka, so I’m probably biased.

Thanks, particularly, for the ripening/aging info. As I find my first pears, this will really help.

LikeLike

Katherine, this blog is always fantastic, but I especially love the posts on pears and strawberries. I can always point to your site as a justification for the fact that botanists like to dissect our fruit salad before we eat it!

LikeLike

I love this page.it contains learned materials

LikeLike

Pingback: The Extreme Monocots | The Botanist in the Kitchen

Pingback: A holiday pineapple for the table | The Botanist in the Kitchen

It appears to me that stone cells continue to grow and/or proliferate in the skin of stored d’anjou and comice pears. Is this possible?

LikeLike

Sounds reasonable to me. Stored pears are still metabolically active, so I don’t see any reason that the stone cells couldn’t continue to build their walls. Cool observation!

LikeLike

Pingback: Kiwifruit 2: Why are they green? | The Botanist in the Kitchen

Pingback: 11 Health Benefits of Pears You Need to Know About Now

There were hard, tan colored granules almost identical to sand underneath the skin of a red anjou pear, that wiped away from the skin easily. The pear otherwise appeared and tasted normal. Should I be worried?

LikeLike

No, no need to worry. As part of the ripening the stone cells are more evident because they separate from the rest of the flesh. As a reader notes above, the stone cells may even get larger.

LikeLike

I make pear wine, vinegar and brandy and simple syrup and use it to make a shrub cocktail the wine i just drink

LikeLike

Pingback: How Do You Know When A Conference Pear Is Ripe?