A batch of lemon balm-lemon verbena syrup reminds Jeanne of the multiple evolutionary origins of lemon flavor.

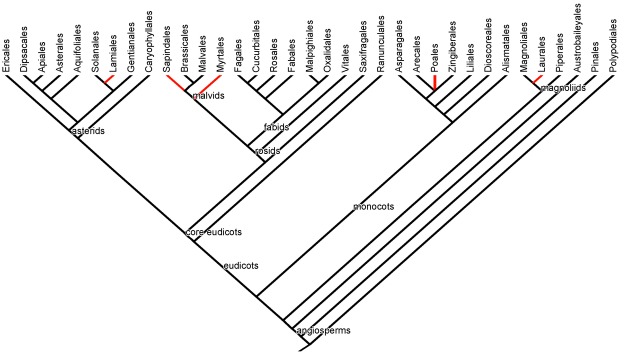

The citrus lemon itself is only one of many plant species that lends its namesake flavor or fragrance to our food and drinks. Lemon flavor primarily comes from a few terpenoid essential oils: citral (also called geranial, neral, or lemonal), linalool, limonene, geraniol, and citronellal. The production of one or more of these essential oils has independently evolved multiple times in species on widely separated branches of the plant phylogeny (see figure).

The citrus lemon itself is only one of many plant species that lends its namesake flavor or fragrance to our food and drinks. Lemon flavor primarily comes from a few terpenoid essential oils: citral (also called geranial, neral, or lemonal), linalool, limonene, geraniol, and citronellal. The production of one or more of these essential oils has independently evolved multiple times in species on widely separated branches of the plant phylogeny (see figure).

Phylogeny of plant taxonomic orders with edibles (click the tree to enlarge). Orders with species with lemony essential oils are highlighted in red. For a refresher on reading this phylogeny, please see our food plant tree of life page.

I was reminded of this extraordinary evolution of lemoniness today when I made a syrup (recipe below) from lemon balm (Melissa officinalis), a mint (family Lamiaceae), and lemon verbena (Aloysia citrodora), in the verbena family (Verbenaceae). The mints and the verbenas are closely related families within the order Lamiales, however, so combining them together did not produce a particularly phylogenetically extreme lemony syrup. Many other species in the mint family produce lemony essential oils, such as lemon basil (Ocimum spp.), lemon thyme (Thymus spp.), and lemon mint (Monarda spp.). And the sand verbenas (Abronia spp.) growing on the sand dunes on the California coast have a lemony aroma.

Lemongrass (photo from Wikipedia)

Moving away from the Lamiales, lemony essential oils are most spectacular, of course, in the citruses (family Rutaceae, order Sapindales). Several of the Australian Myrtaceae species (order Myrtales) are lemony and used as a spice, including lemon myrtle (Backhousia citriodora), lemon gum (Corymbia citriodora), and lemon tea tree (Leptospermum polygalifolium). The lemony leaves and fruit of Litsea cubeba, in the bay family (Lauraceae, order Laurales), are locally popular as a spice in its native tropical Asia. Popular now the world over, however, are other tropical Asian natives the lemon grasses, some 55 species of grasses in the genus Cymbopogon (family Poaceae, order Poales). Cymbopogon citratus is the most popular culinary species. Commercial citronella essential oil (the real stuff in natural insect repellent) is distilled from C. nardus and C. winterianus. In all of these diverse taxa, the lemony essential oils serve as defense compounds against pathogens and herbivores. This is not to say that these plants all taste the same, which of course they don’t. They all have their own unique flavor compounds as well, and the relative proportions of the lemony terpenoids vary.

While the lemony essential oil compounds themselves have independently evolved numerous times, the structures that plants use to store and deploy them against marauders are highly variable across the plant tree of life. Citrus leaves and fruit concentrate their essential oils in oil glands. Specialized cells cluster together, synthesize the oils, and secrete them into the space between the cells, forming a chamber (gland) filled with oil (Thomson et al. 1976). The oil glands are so large that you can see them as translucent spots if you hold a citrus leaf up to the light.

The oil glands in citrus are found in almost all plant structures but are most abundant in the outer fruit rind (zest). Many species in the Myrtaceae also have oil and resin canals or specialized storage cells, although these are structurally different from those in citruses. The essential oils in lemongrass leaves are stored in specialized cells nestled between the vascular bundles in the spongy mesophyll, beneath the photosynthetic tissue. The cell walls of these lemongrass oil cells are lignified (woody), perhaps contributing physical as well as chemical defense against marauding herbivores (Lewinsohn et al. 1998).

The verbenas and the mints in the Lamiales have my favorite essential oil delivery system—trichomes. Trichomes are hair-like growths on the outside surface of plant structures. Trichomes are responsible for the fuzziness of kiwifruits. Like epicuticular wax, trichomes take on particular shapes and forms in different plant lineages and species. The hooked trichomes on the leaves of bean plants (Fabaceae), for example, feel like sandpaper if you rub your hand over them. These hooks may serve the plant in part by slowing insect herbivores down, if their efficacy at catching bedbugs is any indication. The leaves of mints and verbenas have two kinds of trichomes. The first kind is hair-like, with either no branches, as in lemon balm, or with multiple branches, as in fellow mint-family member lavender (Lavandula spp.). These trichomes may help cool the leaf by deflecting excess solar radiation. The other trichomes on these leaves are glandular hairs. These trichomes fill with essential oil and sit like squat little water balloons on the surface of the leaf. The flowers, too, are covered in glandular hairs. The glandular and hair-like nonglandular trichomes on mint leaves are visible in the scanning electron micrograph picture below.

Scanning electron micrograph of peppermint trichomes (magnified to 742 times actual size). The glandular trichomes full of essential oil are yellow. The hair-like trichomes look like spikes. Photo source here.

When you rub a verbena or mint-family leaf between your fingers, you rupture the glandular trichomes and release some of the most fragrant substances this planet has to offer. They may be repellent to bugs, but hardly to us.

Fresh herb syrup

Lemon thyme on the left, French thyme on the right

There are two different ways I make a sweet syrup out of fresh herbs. In the first, I start by making a strong infusion (“tea”) out of the herbs. I usually barely cover them with water in a pot, bring it to a boil, then turn the heat off and let it steep for however long it needs. The steeping is definitely up to you, but you should start tasting it after one minute. Steeping leaves like lemon balm and lemon verbena for more than 5 minutes or so will start to draw out some of the bitter and dark tannins from the leaf (remember the essential oil is on the surface), which may be fine with you, but you should just keep checking and tasting. Then, I strain out the leaves and add an equal volume of sugar to the remaining liquid in a saucepan and stir to dissolve the sugar while I bring it to a boil. The second method is to measure or guess how much liquid I’ll need to cover the herbs packed into the bottom of a saucepan, then add an equal volume of sugar to that amount of warm/hot water, stir it to dissolve the sugar, then pour it over the herbs, bring it back to a boil, turn off the heat, let it steep, then strain. Either way, stirring in about a tablespoon of vodka or brandy per cup of syrup will help preserve it for about a month in the fridge if you’re not going to can it or freeze it. I like stirring a little of this syrup into club soda to make a grown-up soda, and it’s also good incorporated into or onto ice creams or sorbets or drizzled over an almond cake. Update: Since originally writing this recipe, I think I’ve landed on a better way to make syrup out of species with glandular trichomes (mints, verbenas). I decide first what volume of water I want to use, based on the amount of herbs I have available and the desired strength of the syrup. I tend to make a very concentrated, strong syrup, and I don’t as yet have an exact herb:liquid ratio measured, but I tend to use about half as much liquid as fresh leaf volume. The amount of sugar to use is still equal to the volume of water. I add the sugar to the fresh leaves in a large steel or ceramic bowl and thoroughly massage the leaves and sugar together with my hands for a few minutes. The idea here is to rupture all of the glandular trichomes and mix the sugar and essential oils together and begin to dissolve the sugar with the essential oil and liquid released from the partially macerated leaves. It’s the same logic behind pounding the mint and sugar together in a mojito or mint julep. I bring the water to a boil and immediately pour it onto the leaf-sugar mixture and immediately begin stirring to dissolve the sugar. As soon as the sugar is dissolved, which should happen within 2 minutes, I strain it back into a saucepan, bring it to a boil again, then pour it into sterilized glass canning jars and put lids on it. Then you can decide what you want to do with it; that is, can it while it’s still hot, or let it cool and freeze it or refrigerate it, with or without booze. We usually blow through ours pretty quickly, so storing it in the fridge works fine for us, even without adding some booze (brandy, vodka) to it, which would extend its shelf life in the fridge. If you want to can it, follow instructions for low-acid jam or jelly. If you want to freeze it, consider freezing it in ice cube trays, so it can be doled out in cute individual-serving-sized morsels.

References

Gattuso, S., C. M. van Baren, A. Gil, A. Bandoni, G. Ferraro, and M. Gattuso. 2008. Morpho-histological and quantitative parameters in the characterization of lemon verbena (Aloysia citriodora palau) from Argentina. Boletín Latinoamericano y del Caribe de Plantas Medicinales y Aromáticas 7: 190-198.

Lewinsohn, E., N. Dudai, Y. Tadmor, I. Katzir, U. Ravid, E. Putievsky, and D. M. Joel. 1998. Histochemical localization of citral accumulation in lemongrass leaves (Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf., Poaceae). Annals of Botany 81: 35-39.

Stewart, A. 2013. The drunken botanist: the plants that create the world’s great drinks. Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, N.C.

Svoboda KP and RI Greenway. 2003. Lemon scented plants. International Journal of Aromatherapy 13: 23-32.

Thompson, W.W., K. A. Platt-Aloia, and A. G. Endress. 1976. Ultrastructure of oil gland development in the leaf of Citrus sinensis L. Botanical Gazette 137: 330-340.).

Pingback: Lemon Balm (Balm) | Find Me A Cure

Those oil glands in citrus leaves can be used to make an easy appetizer. Just put a slice of mild nutty cheese (like a garrotxa, p’tit Basque, colby, or Monterey jack) on top of a clean lemon leaf, melt it under the broiler, and serve. Eat the cheese off the leaf, but don’t eat the leaf. The oil glands open up under the heat and the lemon oils seep into the melted cheese fat. Mmmmm.

LikeLike

Fascinating story – next time I pick up a lemon, I will do it with a whole lot more reverence!

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

Pingback: Hollies, Yerba maté, and the botany of caffeine | The Botanist in the Kitchen

Pingback: Find Me A Cure

Pingback: Taking advantage of convergent terpene evolution in the kitchen | The Botanist in the Kitchen

Pingback: Winter mint | The Botanist in the Kitchen

Hai introduce me from Indonesia, I read the article you wrote about the family of a mint plant

in our country the plant is used to increase milk in nursing mothers. The trick to cooking the leaves is by using coconut milk combined with meat and spice turmeric. This is already common practice for generations.

LikeLike

Pingback: Carrot top pesto through the looking glass | The Botanist in the Kitchen

Pingback: Kiwifruit 1: Why are they so fuzzy? | The Botanist in the Kitchen

Pingback: Spruce tips | The Botanist in the Kitchen

Pingback: Leave It To Botanists To Turn Cooking Into A Science Lesson : The Salt : NPR - Best Special News

Pingback: Leave It To Botanists To Turn Cooking Into A Science Lesson | 1 News Net

Pingback: Leave It To Botanists To Turn Cooking Into A Science Lesson : The Salt : NPR

Pingback: Leave It To Botanists To Turn Cooking Into A Science Lesson-Times of News Italy

Pingback: Leave It To Botanists To Turn Cooking Into A Science Lesson – BBC World News

Pingback: Leave It To Botanists To Turn Cooking Into A Science Lesson | America On Cue

Pingback: Leave It To Botanists To Turn Cooking Into A Science Lesson | Earth Eats - Indiana Public Media

How does lemon balm deliver essential oils when it hardly has any (thus the astronomical cost of Melissa essential oil)? Surely there is a water-soluble lemony constituent.

LikeLike

The essential oil is synthesized in the glandular trichomes on the epidermis and is readily released by steam distillation, which ruptured the trichromes and decreases the oil viscosity. No water solubility is needed. Trichome density on all Lamiaceae varies across plants for a variety of reasons. I haven’t read a study about Melissa species having categorically lower trichome density or size, but it could be the case. Interesting!

LikeLike

Anecdotally I wouldn’t describe my own lemon balm plants as having hardly any oil.

LikeLike

Pingback: Sage, rosemary, and chia: three gifts from the wisest genus (Salvia) | The Botanist in the Kitchen