Walnuts may not seem like summer fruits, but they are – as long as you have the right recipe. Katherine takes you to the heart of French walnut country for green walnut season.

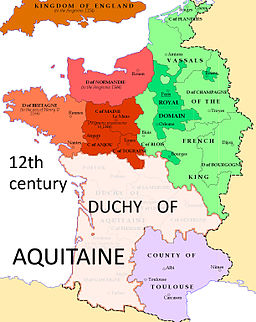

English walnuts do not come from England. The English walnut came to American shores from England, but the English got them from the French. The (now) French adopted walnut cultivation from the Romans two millennia ago, back when they were still citizens of Gallia Aquitania. Some people call this common walnut species “Persian walnut,” a slightly better name, as it does seem to have evolved originally somewhere east of the Mediterranean. But the most accurate name for the common walnut is Juglans regia, which means something like “Jove’s kingly nuts.” I think of them as queenly nuts, in honor of Eleanor of Aquitaine, because if any queen had nuts, she certainly did. During her lifetime the Aquitaine region of France became a major exporter of walnuts and walnut oil to northern Europe, and it remains so more than 800 years later.French walnut culture may actually predate the Romans by tens of millennia, as archeological and paleobotanical evidence places walnut trees and early modern humans in the same locations at the same time. The Périgord region of Aquitaine in south western France is home to the original Cro-Magnon site and some of the richest archeological remains of early modern humans in Europe. Prehistoric pollen deposits show that walnuts grew wild in this same area, and that isolated walnut populations in France and Spain may have survived the last ice age (Carrion & Sanchez-Gomez 1992; refs in Henry 2010). Thus the earliest modern humans in Europe could have gathered the nuts. It probably would have been worth their effort since even wild walnuts are abundant, large, nutritious, caloric, and easy to process.

But did they? The romantic notion that Cro-magnons gathered walnuts has passed from mere plausibility into cherished legend in French walnut country. The professional organization of Périgord nut producers suggests that the same people who adorned the walls of Lascaux with animal paintings 17 thousand years ago may have enjoyed their roasted aurochs encrusted with a golden layer of crushed walnuts.

(I eventually found a likely source for this claim: a brief mention, in a 1963 note in the bulletin of the French Prehistorical Society, of broken walnut shells in a cave dated to about 12 to 14 thousand years before present.) Whatever their role in early modern human diets, there is solid evidence that walnuts gained importance in Roman times (Figueiral & Séjalon 2013), and today they are deeply embedded in the culture of south west France.

From Jove to John

On an afternoon in late June, deep in French walnut country, I stood on the street and wondered aloud about “nut wine.” The street was the only navigable one in La Roque-Gageac, a tiny medieval town carved into a cliff face over the Dordogne river. Within a block I had already seen vin de noix, walnut wine, offered at two shops and the restaurant of the hotel where our small band of pilgrims would stay that night. Our friend Pascal explained that walnut wine was a regional specialty, made at home by just about everyone in his grandparents’ generation and many generations before them. When the woman who greeted our table at the hotel told us that they made their own vin de noix following an old recipe, I had to try it. It was served slightly cool, cellar temperature, but it tasted warm and rich and honey-spiced. After one sip I knew I would be making this at home myself.

As it turns out, late June was the perfect time of year to discover nut wine. Vin de noix is not fermented walnut juice. It is Bordeaux wine that has been augmented with crushed macerated young walnut fruits, green husks and all. The recipe also includes eau de vie, among other things, and requires several months to mellow (see recipe below). According to tradition, the best young walnuts are harvested around the feast day of St. Jean-Baptiste on the 24th of June. After that, the shells inside start to harden, and cutting them becomes impossible or dangerous.

What is a walnut?

In their natural state, the sculptured shells of walnuts are covered in a thick green rind or husk, derived from the walnut flower. Since the husk is sticky, stinky, and makes terrible stains, it is removed before walnuts are sent to market. To make walnut wine, then, you have to find your own walnut tree. More on that below.

The next most natural and inclusive form of walnut would be those still in the shell. You might buy walnuts in the shell if you like the way they look in a bowl or want to slow the pace of your snacking. About a third of US production is sold this way (NASS 2014). The hard shells are derived from the ovary, so in botanical terms the shells are part of the fruit proper (pericarp, and specifically endocarp). The shell layer starts out as living tissue whose cells have soft walls and the capacity for growth. As the walnut fruits reach full size, however, the specialized cells of the shell start to thicken their own walls by adding layers from the inside, until the living part of each cell is reduced to a tiny little pocket inside a ridiculously well defended fortress. Eventually the cells cannot communicate with the outside world and they die. If you harvest walnuts right after John-the-Baptist day, though, the shell will still be alive and soft, and the nuts will be easy to cut.

The most prized part of a walnut fruit is the rich oily seed inside. The fat brain-shaped walnut halves are mostly the cotyledons,  which would have become the first leaves of a walnut seedling had the seed been allowed to germinate. [As reader Dianne points out below, the cotyledons in this species stay below ground and do not photosynthesize, but rather provide nutrients to the seedling. You would not see them above ground, as with a common bean cotyledon, for example.] The central body of the walnut embryo lies along the tear-drop shaped area where the two halves were joined in the shell. The seed is covered with a thin brown seed coat, shot through with branching veins that once carried nutrients to the developing seed. That seed coat also contains a lot of phenolic compounds, and at least one of them can leach into dough and give bread a purple cast.

which would have become the first leaves of a walnut seedling had the seed been allowed to germinate. [As reader Dianne points out below, the cotyledons in this species stay below ground and do not photosynthesize, but rather provide nutrients to the seedling. You would not see them above ground, as with a common bean cotyledon, for example.] The central body of the walnut embryo lies along the tear-drop shaped area where the two halves were joined in the shell. The seed is covered with a thin brown seed coat, shot through with branching veins that once carried nutrients to the developing seed. That seed coat also contains a lot of phenolic compounds, and at least one of them can leach into dough and give bread a purple cast.

Although we rarely see it, the husk (or “hull”) is the most interesting part of our walnut story. For one thing, the husk is complicated because it is composed of several different types of tissue fused together in a way that undermines its straightforward classification as a fruit.

If the husk were derived from ovary tissue alone, the fruit would be called a drupe; however only the very inner part of the husk comes from the ovary. Surrounding that layer are four thick sepals fused side-to-side, which are in turn covered by a layer of fused bracts.

To me, the husk of a young fruit looks like a thick green sweater over a green shirt, with the tips of the sepals emerging liked a popped collar. (Stretching the comparison, the ovarian layer might be the undershirt you never see.) All that extra-ovarian tissue has led most botanists to classify walnuts as pseudo-drupes. In this way, the walnut is similar to its cousin, the pecan, albeit simpler. (The pecan husk splits open, further complicating the fruit type. See here for more of that story. It also turns out that J. regia is probably the only walnut species with a splitting husk. Things are getting really complicated now.)

Loving and hating the husks

The keepers of nut lore fondly repeat the saying that “Nothing is lost from the Perigord walnut except the sound of its cracking.” (Rien n’est perdu dans la Noix du Périgord sauf le bruit qu’elle fait en se cassant.) The nutmeats, shells, and husks all have their uses, as it turns out.

Walnut husks are sticky with resinous glandular hairs, and their flesh is full of the compounds juglone and gallic acid. Juglone is a famously bad party guest because it kills other plants and stains everything it touches. Juglone is present throughout the walnut tree, from leaves to roots, and the soil under a walnut tree can be extremely toxic to tomatoes and a wide array of other plants. Black walnuts (J. nigra), native in much of the eastern US, are especially potent. There were a couple of black walnut trees in the back yard of my childhood home, encroaching upon the most obvious spot for a vegetable garden. Our tomatoes did well in fresh soil in a raised bed, unless their roots found their way into the deeper walnuty soil. Then, in my dad’s words, they looked like they’d been “hit with a blow torch.” I also remember stained bare feet and spots on the carpet, but it was worth it – those black walnuts tasted like caramel and anise.

Gallic acid is a much nicer component of the husk. It is a phenolic acid found in many plants, including tea leaves, grape skins, and oak bark. It is astringent and seems to make up the largest fraction of what leaches out of the walnut husks and into our nut wine, with juglone also contributing some flavor and color (Stampar et al. 2006, Mrvcic et al. 2012). Although the etymology gods missed a great opportunity, gallic acid is not named for the people of Gallia Aquitania and their famous walnuts. It was originally obtained from oak galls.

Making walnut wine

As soon as I returned from France in early July I hurried to collect my own green walnuts. Walnut trees grow abundantly along the creek beside the public trail where I run, and their fruits were still small and green. These trees are not English walnuts, but the descendants of native California walnuts (Juglans hindsii) planted by the 19th century owners of the parcels along the creek.

Making vin de noix is simple, although you need good tools. As long as the shells are still soft, they are not hard to cut, but a large sharp knife and a solid cutting board are essential. I found out the hard way that I should have worn gloves and an old apron, since there’s no getting around the juglone. I spent two weeks hiding my henna-colored thumbs. The stains looked especially nasty because Juglone has a way of finding dead skin – cuticles, fingerprint ridges, the stuff right under your nails, and the rough places on the sides of your fingers. A pumice stone and patience help.

Vin de Noix

One bottle (750 ml) of ordinary Bordeaux wine

200 g sugar (approximately 1 cup)

100 ml (2 mini bottles) of Poire Williams or pear-flavored vodka

4 green walnuts, quartered

a cinnamon stick

Collect the walnuts the last week of June. Traditionalists prefer June 24th, St. Jean-Baptiste day; pagans may opt for the summer solstice. As the planet warms, collecting earlier in June will probably be necessary.

Wash the walnuts and quarter them with a large butcher’s knife. They will stain your fingers and cutting board a greenish brown color unless you wear gloves and protect the board with thick paper.

Pour all of the ingredients into a pitcher and stir to dissolve the sugar. Cover the pitcher and let the mixture sit for a Biblical 40 days and 40 nights of soaking. Stir once a week and remove any floating fruit flies.

Strain the mixture, put it back into an empty wine bottle, and seal it with a cork. Allow the wine to mellow until Christmas or the winter solstice, whichever suits your worldview.

Serve as an aperitif and make a toast to old friends and summer adventures

References

Carrion, J.S. and P. Sanchez-Gomez (1992) Palynological data in support of the survival of walnut (Juglans regia L.) in the western Mediterranean area during last glacial times. Journal of Biogeography 19: 623-630

Cheynier André. Présence du noyer à l’époque azilienne. In: Bulletin de la Société préhistorique de France. 1963, tome 60, N. 1-2. p. 74.

doi : 10.3406/bspf.1963.3885

Figueiral, I. and P. Séjalon (2013) Archaeological wells in southern France: Late Neolithic to Roman plant remains from Mas de Vignoles IX (Gard) and their implications for the study of settlement, economy and environment. Environmental Archaeology

Henry, A. G. (2010) Plant foods and the dietary ecology of Neandertals and modern humans. PhD dissertation for The George Washington University

Mrvcic, J. et al. (2012) Spirit drinks: a source of dietary polyphenols. Croat. J. Food Sci. Technol. 4: 102-111

National Agricultural Statistics Service of the USDA (2014)

Stampar, F, et al. (2006) Traditional walnut liqueur – cocktail of phenolics

Food Chem., 95 (2006), pp. 627–631

Other vin de noix recipes:

http://www.atelierdeschefs.fr/fr/recette/15505-vin-de-noix.php

http://lacuisinedelilly.canalblog.com/archives/2014/06/23/30112218.html

http://tomatesansgraines.blogspot.com/2014/06/vin-de-noix-maison.html

What fantastic blog! I love how it is written along with the amazing content and referenced too! Brilliant. Can I add you on Feb? I’m sure your posts are just as interesting

LikeLike

Thanks for reading. What is Feb?

LikeLike

Great post! Makes me very nostalgic, and I cannot wait to get hold of some of this wine and taste it!

Lanier

LikeLike

I loved this post. And I love walnuts. I grew up in a walnut orchard in California which maybe be the reason I’m smitten with these nuts. Do you have any familiarity with Carpathian walnuts? Thanks for another good post.

LikeLike

Thanks, Deborah. My husband grew up in a walnut orchard in California (near Fowler), too. That orchard now grows almonds, though. Carpathian walnuts are a cold-hardy subspecies of English walnuts (J. regia) from western Asia. They’re probably the variety you see planted in the coldest parts of the U.S. and are naturalized (escaped from cultivation, established in the wild) in many areas. A quick look didn’t reveal any taste test results or chemical comparisons of J. regia cultivars that included Carpathian varieties, but Google-able plant merchants report excellent nut quality.

LikeLike

Extremely interesting post. I’ve cooked a great deal with walnuts because I love the flavour, but now I will seek them out when green!

LikeLike

Love the post and something for a future to-do list. I have also heard of small green walnut stored in sugar syrup served as a snack with tea in Azerbaijan. (Not sure of the exact preparation for this item.)

Having worked with Juglans germplasm for several years, I offer the following minor additions and clarifications regarding Juglans regia and the Juglans genus. First, you never see the cotyledons as Juglans species have hypogeal germination. Next, the husk of Juglans regia does split at maturity though this is not true for all or most other Juglans species. Lastly, there are several North American ‘black’ walnut species, J. nigra being one of the most widely distributed and well known. Other North American black walnut species include J. hindsii, J. californica, J. microcarpa, and J. major.

LikeLike

My own statement regarding walnut cotyledons should actually read, “the cotyledons are not the first leaves seen as Juglans species have hypogeal germination”, or something more along those lines.

LikeLike

Thanks for these clarifications, Dianne. The dehiscent husk of J. regia raises interesting questions. Since Carya husks dehisce, it’s not surprising to see the trait appear in Juglans. But I wonder whether dehiscence in this one species was selected by early human gatherers or by natural selection pressures. Do you know? I’ll have to poke around in the paleobotanical literature and see what I can find.

I have made some changes to the post in response to your comments. Thanks for reading and taking the time to help us stay accurate.

KP

LikeLike

The most unusual vegetable I ate on a recent trip to Sichuan China was walnut male inflorescences (catkins), a specialty of the Qiang people. Here is a photo taken by another traveler https://www.flickr.com/photos/saltedlolly/51298703/

LikeLike

Wow. Yet another way in which nothing is left unused from a walnut. Were they good??

LikeLike

Very good. They tasted like walnuts.

LikeLike

Pingback: Nibbles: Palms, Walnuts, Gardening game, Measuring biodiversity, Promoting biodiversity, Restoring land, Honeybee evolutions, Amaranth recipes, Cider communication

Pingback: Nibbles: Palms, Walnuts, Gardening game, Measuring biodiversity, Promoting biodiversity, Restoring land, Honeybee evolutions, Amaranth recipes, Cider communication | Gaia Gazette

http://ceviz.biz/ walnut

LikeLike

Pingback: Kiwifruit 1: Why are they so fuzzy? | The Botanist in the Kitchen

Pingback: Spruce tips | The Botanist in the Kitchen

Not sure where the line is crossed between Walnut Wine (consumed freely) and Walnut Tincture – consumed limited as a antimicrobial, blood cleansing, detoxifying tonic… I put 99 hulls (late when shell formed) after extracting shell in 100 proof vodka and soaked 2 months. I drained /bottled – now wonder if I can consume ‘shots’/social or only ‘drops’/medicine… (?)

LikeLike

Personally I think taste alone would limit consumption to small doses. It could be an interesting bitters when mixed with other things. As for its toxicity I have no idea but would use caution.

LikeLike

Pingback: Sheltering in the kitchen with oatmeal | The Botanist in the Kitchen

Love this post! Can’t wait till next spring so I can try my hand at walnut wine. Thank you for this blog, Katherine and Jeanne. It’s wonderful!

LikeLike

Thanks for reading, Nancy! I’ll have to give you a glass sometime. I made walnut liqueur this year (vodka, walnuts, spices), and it’s much more severe, but still quite good.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Botanist in the Root Cellar | The Botanist in the Kitchen