Infinity scarves? No. They won’t keep doctors away. Apples are the ultimate everyday accessory (fruit). Katherine explains where the star in the apple comes from. Could it be due to a random doubling of chromosomes? We also give readers the chance to test their apple knowledge with a video quiz.

Although apples are not particularly American – nor is apple pie – they color our landscape from New York City to Washington State, all thanks to Johnny Appleseed. Or so goes the legend. Everyone already knows a lot about apples, and for those wanting more, there are many engaging and beautifully written stories of their cultural history, diversity, and uses. See the reference list below for some good ones. There is no way I could cover the same ground, so instead I’ll keep this post short and sweet (or crisp and tart) by focusing on apple fruit structure and some interesting new studies that shed light on it.

Of course if you do want to learn more about apple history but have only 5 minutes, or if you want to test your current knowledge, take our video quiz! It’s at the bottom of this page.

Apple structure

Depending on your approach to eating apples, you may not actually consume any fruit at all. If you nibble the outer part, warily avoiding the core, then you might be missing the true fruit entirely. If, on the other hand, you eat all the way down to the core (or even eat the core itself like the Foodbeast guy) then you are definitely getting to the fruit.

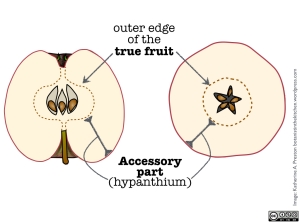

Mature apple fruits in longitudinal and cross-section. The “true fruit” is the part derived from the ovary. It is visible in a cut apple as a ring of vascular tissue. Click to enlarge.

Apples are pomes, meaning that what’s commonly considered the “true” fruit – the part derived from the ovary – is buried inside a large fleshy hypanthium that developed from other apple parts. The bulk of what we eat is that sweet and crunchy hypanthium (Greek for “under the little flower”). In spite of what some people assume, though, the actual ovary is not just the plasticky bits that surround the seeds and form the star in a cross-cut apple. Most of the ovary is fleshy and blends almost seamlessly into the rest of the apple. Its boundary is subtle, but you can see it in a cut apple as a ring of vascular tissue (veins) surrounding the core.

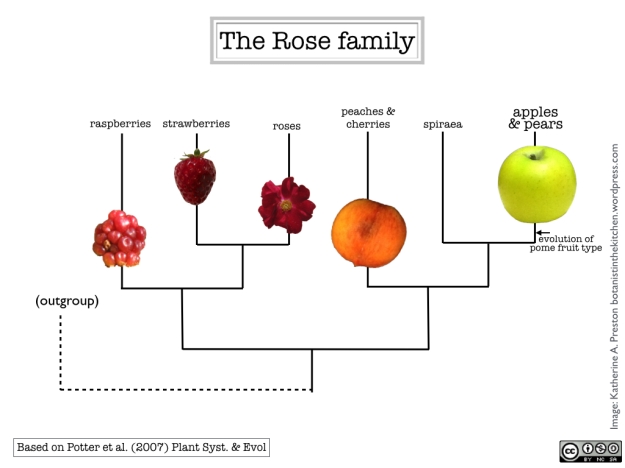

Pome-like fruits are found in apples, pears, quinces, loquats, and medlars, which are all members of the same clade (branch) within the rose family (Rosaceae).

Pomes of Heteromeles arbutifolia, with a penny for scale. The fruit at bottom left still has an old petal attached at the distal end, illustrating the inferior position of the ovary. Click to enlarge.

Also in the clade are typically wild-growing or ornamental plants such as hawthorne, cotoneaster, Heteromeles, Pyracantha, Photinia, and Raphiolepis. All of these species have flowers with inferior ovaries – ovaries buried within a hypanthium – and are unique within the rose family in this respect.

It’s easy to spot an inferior ovary because the leftover flower parts (or their scars) can be found opposite the stem on the mature fruit. In the rose family, a useful comparison is between apples and cherries or strawberries.

Cherry flowers have superior ovaries, visible within the floral cup. Apple flowers’ inferior ovaries are buried within a hypanthium and fused to it. Click to enlarge

The sepals and petals of a cherry generally fall off, but they leave scars in a ring close to where the stem meets the fruit. The sepals of a strawberry always persist, and petals can often be found on fresh berries, right around the stem.

By contrast, the floral bits of an apple are at the “bottom,” opposite the stem end. There you can see a ring of sepals surrounding a bunch of pollen-bearing stamens and sometimes even the styles that lead down to the ovary. Occasionally a shriveled petal remains there. Sometimes that little floral hole is filled with spider webs or dirt, but not as often as some people fear. And indeed I have noticed that some people do fear apples just a little bit, or at least eye them suspiciously. I don’t think we can blame the fate of Adam and Eve or the evil queen in Snow White for apples’ tainted reputation. I honestly think it’s anxiety over what might lurk in the little eye at the bottom of the fruit.

What we have learned from the apple genome

A pome is a type of fruit, and regular readers will know that fruit types are artificial categories with fuzzy boundaries and no regular or necessary relationship to evolutionary history or phylogenetic relatedness. That said, close relatives often produce the same type of fruit, and there are some fruit types restricted by convention to specific plant families or clades. Citrus fruits (hesperidia) are a good example of fruit type mapping perfectly onto a natural plant group.

Within the rose family, the occurrence of pome fruits does reflect evolutionary history: pomes are present in only one clade, the apple tribe (called the Pyreae or Maleae). Intriguingly, this fruit type may be the result of a huge genetic shift within the family about 50 million years ago (Velasco et al. 2010). In 2010, a team of researchers published a draft of the apple genome, showing that the ancestor of the apple tribe experienced a duplication of its entire set of chromosomes (Velasco et al. 2010). The duplication was followed by an expansion and diversification of a set of genes (MADS-box genes) that control flower and fruit development by regulating the expression of other genes.

But how do a few genetic switches turn the ancestral dry fruit into an apple? It turns out that one of these MADS-box genes is particularly important for making a fleshy fruit, and that when it is experimentally turned off, the resulting fruit is dry. Even more impressive, though, is that the same gene is also required for other fruit qualities – exactly those qualities that would make a fleshy fruit attractive to animal dispersers: color, aroma, and sugar content (Ireland et al. 2013). How do you like them apples?

All you wanted to know about apples in 5 minutes

References and further reading

Ireland, H. et al. (2013) Apple SEPALLATA1/2-like genes control fruit flesh development and ripening. Plant Journal 73: 1044-56.

Jacobsen, R. (2014) Apples of Uncommon Character: Heirlooms, Modern Classics, and Little-Known Wonders. Bloomsbury USA

Juniper, B.E. & Mabberley, D. J. (2006) The Story of the Apple. Timber Press

Pollan, M. (2001) The Botany of Desire: A Plant’s-Eye View of the World. Random House

Potter, D. et al. (2007) Phylogeny and classification of Rosaceae. Plant Systematics & Evolution 266:5-43.

Spjut, R. (1994) A Systematic Treatment of Fruit Types. NYBG.

Velasco, R. et al. (2010) The genome of the domesticated apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.). Nature Genetics 42: 833–839

Excellent

JV

John Valenzuela

415 246 8834

@ValenzuelaJohn

cornucopiafoodforest.com

-sent by mobile device

>

LikeLike

Somebody needs to craft a short pome for the best inferior fruit, ever. I always look forward to your posts — thanks.

LikeLike

Thanks, Colin! It’s funny you say that. One of my best friends in college was from Kentucky, and she said “pome” for poem. She was a Comp Lit major, so there were ample occasions to tease her. She has been gone more than half my lifetime, but every time I write about pomes I think of her fondly and miss her.

LikeLike

To give you some idea of what’s been lost the Apples of New York (1905) said there were around 1600 varieties grown in the state. Highly recommend you find and try Northern Spys.

LikeLike

Thank you, Katherine, for a pleasantly informative post! I DO eat an apple a day and have switched grocery stores plenty of times solely due to the quest for high apple quality. So I was interested to learn about the botanical structure of apples (and embarrassed myself about how little I knew). I loved the video and will share your blog to other food-ophiles! I learned a lot! But I do have a question: What makes some apples so crisp and others mushy/mealy? Katey Brown

LikeLike

Thanks, Katey! And I’m glad you asked about apple texture. I am looking into that as part of a second apple post. Apples and peaches have different ripening profiles, but I suspect that some similar things are going on to determine texture. I wrote about peaches a couple of years ago, and you might find something interesting there. Or at least something familiar https://botanistinthekitchen.wordpress.com/2012/08/27/do-peaches-belong-in-the-fridge/

Thanks again!

LikeLike

Pingback: Sugar | The Botanist in the Kitchen

Fascinating, finally answers to all of my questions about apples. Now I can see why it is better to eat an apple as it is, and not cuting it up with a knife and peeling the skin off.

LikeLike

Pingback: A holiday pineapple for the table | The Botanist in the Kitchen

Pingback: Sage, rosemary, and chia: three gifts from the wisest genus (Salvia) | The Botanist in the Kitchen

Pingback: The Botanist in the Root Cellar | The Botanist in the Kitchen

Very Cool Blog Post

LikeLike

Great read tthankyou

LikeLike