This month we introduce a new feature to the Botanist in the Kitchen: Botany Lab of the Month, where you can explore plant structures while you cook. In our inaugural edition, Katherine explains why she would like to add her nominee, Solanum tuberosum, to the list of white guys vying for Best Supporting Actor.

In one of this year’s biggest and best movies, Matt Damon was saved by a potato, and suddenly botanists everywhere had their very own action hero. It’s not like we nearly broke Twitter, but when the trailer came out, with Damon proclaiming his fearsome botany powers, my feed exploded with photos of all kinds of people from all over the world tagged #Iamabotanist. The hashtag had emerged a year earlier as a call to arms for a scrappy band of plant scientists on a mission to reclaim the name Botanist and defend dwindling patches of territory still held within university curricula. Dr. Chris Martine of Bucknell University, a plant science education hero himself, inspired the movement, and it was growing pretty steadily on its own. Then came the trailer for The Martian, with Matt Damon as Mark Watney, botanizing the shit out of impossible circumstances and lending some impressive muscle to the cause. The botanical community erupted with joyous optimism, and the hashtag campaign was unstoppable. Could The Martian make plants seem cool to a broader public? Early anecdotes suggest it’s possible, and Dr. Martine is naming a newly described plant species (a close potato relative) for Astronaut Mark Watney.

In the film, that potato – or actually box of potatoes – was among the rations sent by NASA to comfort the crew on Thanksgiving during a very long mission to Mars. After an accident, when the rest of the crew leaves him for dead, Watney has to generate calories as fast as he can. It’s a beautiful moment in the movie when he finds the potatoes. In a strange and scary world, Mark has found a box of old friends. They are the only living creatures on the planet besides Mark (and his own microbes), and they are fitting companions: earthy, comforting, resourceful, and perpetually underestimated. At this point in the movie, though, the feature he values most is their eyes.

What is a potato?

Potatoes (Solanum tuberosum) are stem tubers, underground storage structures derived from stem tissue. As we explain elsewhere, potatoes store a lot of energy as starch, an extremely compact mode of storage. Each eye of the potato is a node on the stem capable of giving rise to a branch, which could eventually emerge from the soil and become a green, leafy shoot. A growing potato shoot fuels its early growth by drawing starch from the parent tuber (often mislabeled the “seed”), leaving the older tuber withered and empty. The new shoot meanwhile generates its own set of roots and underground stems (stolons) tipped with tubers. The new photosynthesizing shoot sends sucrose down to its tubers, where the sugar is converted to energy-rich starch and layered into pearl-like granules inside amyloplasts in the tuber’s storage cells. Each generation’s tubers thus give rise to the next generation of leafy shoots.

A closer look at the eyes

Chances are good that you have a potato in your pantry or refrigerator to use for this month’s botany lab. Standard russet baking potatoes have unremarkable eyes, so they aren’t the best specimens for our purposes. If possible, use a smooth-skinned red or yellow potato with prominent eyes. Fingerling potatoes are even better, if you have them, because their long thin tubers are the most obviously stem-like. You don’t need any other tools for this lab because you won’t be cutting anything up. Your potato will stay intact and available for whatever recipe you have in mind.

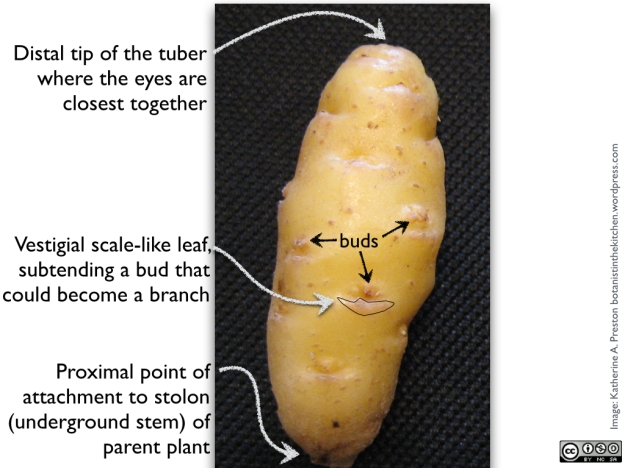

1. The first thing to note about a potato is that it has a proximal end, where it was attached to the parent plant by a thin length of stolon, and a distal end, representing the growing tip of the underground stem tuber. The proximal end often sports a cluster of stringy stolon fibers attached to a little scar. The distal end is where the eyes are close together and where new eyes would have originated had the potato continued to grow.

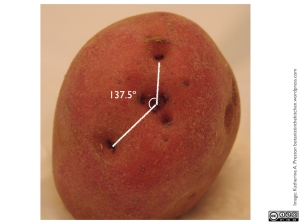

2. Look closely at the distal end. Just as leaves are not randomly arranged on a stem, potato eyes are not scattered haphazardly over the tuber. Instead, they lie in a spiral around the stem. This pattern is less obvious along the fat middle part of the potato, but it can be seen clearly at the distal end where the eyes are close together.

3. Trace the spiral of eyes from the distal tip of the stem. Start by choosing a young eye close to the center of the tip as a starting point. Because new eyes are produced at the tip, the eyes are progressively older the farther they are from that tip. Now locate the next, slightly older, eye on the tuber. Keep moving from eye to eye around the stem, each time choosing the next one in the age sequence. (In the video shown below, the spiral runs counter-clockwise, but your particular spud could run clockwise.)

As you move into the wide part of the potato you will notice that the next eye is located not quite directly across the tuber from the previous eye. In fact, the angle formed by connecting successive eyes to the center of the tip (the vertex) should be about 137.5 degrees, the “golden angle.” This special angle describes the leaf arrangement of many (not all) species, and is derived from the “golden ratio,” which shows up in myriad beautiful objects, from nautilus shells to the Parthenon.

4. Since the eyes are arranged like leaves on a stem, you might wonder whether they themselves are sort of like leaves. Well, sort of. On typical leafy stems, there is a regular spatial relationship between leaves and buds/branches, and the same is true of potato tubers. The lumpy part of the eye is not a leaf, but rather a bud or cluster of buds that can grow out into a green leafy branch. But notice that each bud part of the eye sits in the curve of a thin ridge or lip (click to enlarge Figure 1 above). The ridge may even have a very short scaly extension on it. That ridge is the vestige of a short scale leaf subtending (lying below) the bud/branch. Each eye, then, corresponds to a leaf and its associated bud, which is potentially a branch.

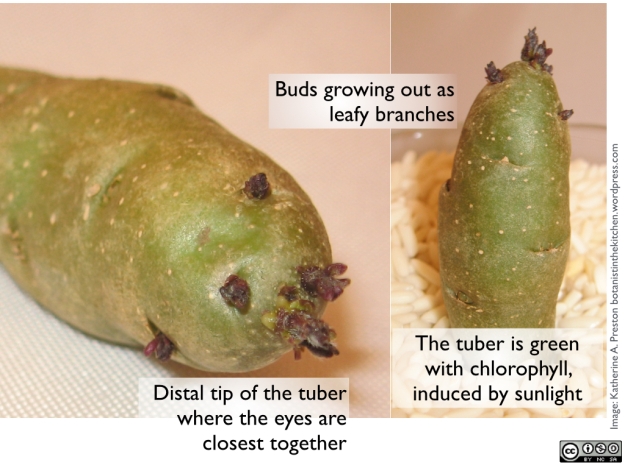

5. Extra credit. If you have a potato to spare, put it out in the sun for a while to sprout and turn green. I’ve kept potatoes like that for nearly a year in my windowsill, without water or soil, and it’s fun to watch the growing shoots gradually draw down the reserves in the tuber.

Potatoes turn green in the sun because the light signals them to produce chlorophyll and start photosynthesizing more sugar. Light exposure also triggers the production of toxic and bitter solanine, which you should avoid eating. Solanine tastes pretty bad, so you probably wouldn’t eat much of it accidentally even if you didn’t notice the chlorophyllous warning sign. Still, if you have obviously green potatoes, either peel them deeply or, better yet, plant them and see what comes up. Who knows when potato farming experience might actually save your life?

My pitch for Best Actor in a Supporting Role

The Oscars (are supposed to) recognize acting achievements and not the function of an actor’s character in the story. But let’s be literal for moment. Of all the nominees for Best Actor in a Supporting Role this year, only a couple of them (Stallone and Ruffalo) played parts that were at all supportive of the protagonists. Mark Watney’s potato friends, however, carried him through “overwhelming odds” both physiologically and psychologically. They gave him calories and nutrition, they gave him hope and inspiration, and they gave him something to worry about besides his own survival. He cared for those plants as true botanists do, recognizing their worth as fellow living creatures and missing them when they were gone.

The hardworking and versatile S. tuberosum showed up in other films this year, too. Although it was disappointingly typecast in Brooklyn, fans will thrill to its cameo appearance in Minnie’s stew, an important plot element in The Hateful 8.

Awesome post, and just in time for Oscars season! Clearly this snub was another grave oversight by the Academy! Two questions, though: Why is the “golden ratio” an advantageous distribution for the branches coming off the potato-stem? And any suggestions for what I should be putting in my stew to make it reliably distinctive just like Minnie’s (along with every other stew ever eaten by Major Marquis Warren, apparently…)?

lanier

LikeLike

Well, first of all, stew (unlike revenge) is a dish best served hot. Second, your knife work matters to the texture and the way the vegetables release flavor into the mix. After that, it’s got to be the spices.

As for the golden ratio, that deserves a full post on its own. Some people have noted that when leaves are arranged this way, the overlap is reduced as much as possible. Others have looked at biophysical forces or diffusible gene products interacting at the stem tip. Maybe we’ll do more on this!

LikeLike

Katherine!!!! I love you!!!! This is the best intro yet!!!! Love it! Aunt Pam

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLike

I’m interested in the potato as I’m very intolerant to it and its whole family (inbcluding tomato, aubergine (aka eggplant), etc, In other words the edible nightshade family. But I can’t understand why I’m intolerant to them. Are there any clues to be had in its botanical makeup, do you know? I can’t eat potatoes at all anymore as they make me very ill (muscle pain being the predominant symptom but the potato and its relatives also cause me to have mouth and throat ulcers.) Any ideas why? It happens with ones that don’t have any green, so I presume is not solanine.

LikeLike

Hi, Val,

I wish I did know why you and others are sensitive to the nightshades. Closely related plants typically share a lot of chemical compounds, yet diversity within a family can also be driven by differences in other compounds. The brassicas leap to mind as an example, along with the celery family. Similarly, raw eggplant is really irritating but raw peppers and tomatoes are (generally) not. I’m sorry you are missing out on one of the more delicious and nutritious parts of the edible rainbow.

On Tue, Apr 12, 2016 at 12:37 PM, The Botanist in the Kitchen wrote:

> Val commented: “I’m interested in the potato as I’m very intolerant to it > and its whole family (inbcluding tomato, aubergine (aka eggplant), etc, In > other words the edible nightshade family. But I can’t understand why I’m > intolerant to them. Are there any clues to be had” >

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, maybe some time in the future someone will discover more about these families of plants and the effects they have on some people. I miss raw tomatoes most – a cheese and tomato sandwich was my idea of heaven! I can eat very well cooked tomatoes but only a little.

LikeLike

Pingback: Maca: A Valentine’s Day Call for Comparative Biology | The Botanist in the Kitchen

You solved a big problem for me! I’m sculpting a giant potato (~4 ft long) for a parade float and was struggling with eye placement. The best part about finding the answer was finding your blog. I’ll be back!

LikeLike

Oh I love hearing why this information was useful! What are you making the potato out of? When I was little I went through a soft-sculpture phase, using my mother’s old panty hose to make lumpy doll faces. They all looked like potatoes, even if their eyes were out of place. Good luck with the float!

LikeLike

I use the pink foam insulation panels from Home Depot–start with a box, layer foam around with Gorilla glue, carve it to shape with a bread knife, sand, glue strips of newspaper on with adhesive that will stick to the foam, then papier mache about three layers on top of that. I’m now at the painting phase–I’ll be sponging a few different shades onto the base color to get the mottled appearance of a potato. It all began when a friend who operates a farmer’s market wanted some giant veggies and fruits for her parade float–the first year I papier mache’d around beach balls, but the second year I decided to do a pumpkin and was looking for something light weight to make it from (and they don’t make beach balls large enough.) This year I’m finally replacing the smaller produce, because they haven’t held up well, and were finally destroyed when snow blew into their shed last winter.

The potato is looking great so far. I just found your email address and will send pictures later.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Botanist in the Root Cellar | The Botanist in the Kitchen