As part of our legume series, the Botanist in the Kitchen goes out to the ballgame where Katherine gives you the play-by-play on peanuts, the world’s most popular underground fruit. She breaks down peanut structure and strategy, tosses in a little history, and gives you a 106th way to eat them. Mmmmm, time to make some boiled peanuts.

Baseball is back, and so are peanuts in the shell, pitchers duels, lazy fly balls, and a meandering but analytical frame of mind. Is this batter going to bunt? Is it going to rain? What makes the guy behind me think he can judge balls and strikes from all the way up here? What does the OPS stat really tell you about a hitter? Is a peanut a nut? How does it get underground? What’s up with the shell? A warm afternoon at a baseball game is the perfect time to look at some peanuts, and I don’t care if I never get back.

Peanuts fit baseball like an old glove fits your hand. Just as players through the ages have taken more clubhouse-friendly monikers, so Arachis hypogaea has many nicknames – peanuts, goobers, goober peas, groundnuts, etc. And fans love peanuts. Legend has it that San Francisco Giants fans leave four thousand pounds – two tons – of peanut shells behind after every home game. Over a season, that adds up to more than 160 tons of shells. (Fortunately, the Giants’ AT&T Park has a massive composting program). Shells make up only about a quarter of a peanut’s total mass, so at every game, six tons of edible peanut parts are consumed by the nearly 42 thousand fans typically in attendance. By my goobermetric calculations, that translates into more than a quarter pound and 700 Kcals of goober peas per person, not including any peanuts taken in as Cracker Jack. Consider that not everyone there is eating peanuts, and you have some fans hitting the peanuts pretty hard. Of course there are fans who are seriously, even dangerously, allergic to peanuts, and many teams now offer peanut-controlled sections for a few games per season. Personally, I like my peanuts best when they are boiled in brine and served in Georgia – just one of the ways you can get them at Turner Field in Atlanta.

Wherever your home team might be, imagine you are sitting there in the stands on a warm lazy day asking yourself “what is a peanut?” Most “nuts” are not botanical nuts, and neither are peanuts. You will have heard that peanuts are “peas,” and that’s mostly right. Arachis hypogaea is in the legume family (Fabaceae), and its botanical fruit type is also called a legume, along with green beans, snap peas, and edamame. The shell of a peanut develops from its ovary (making it a fruit), and it contains the edible peanut seeds inside, surrounded by a reddish brown papery seed coat. So peanuts in the shell are fruits, and we open them up and eat the seeds.

In fact, peanuts are among the rare fruits that develop underground, although they flower above ground. They start as beautiful aerial flowers, shaped like those of its sweet pea cousins, and strikingly bright yellow. Bees love them and occasionally spread their pollen, although the flowers typically fertilize themselves (Leuck & Hammons,1965).

The really weird part comes after pollination, when the flower petals fall off and the ovary (soon-to-be-shell) starts to push itself underground. It’s not the flower stalk (pedicel) that buries the fruit; rather the base of the ovary itself elongates into a structure called the “peg” (Smith, 1950). A recent study (Chen et al. 2015) found literally hundreds of genes involved at different stages in this odd developmental move. Genes that give plants a sense of gravity are important in turning the peg down into the ground. Once there, the tip of the peg uses another few hundred genes to know that it’s dark and that the ovary should start to develop into a fruit.

But developing underground (“subterranean fructification”) is pretty tough on a fruit, and a peanut ovary is exposed to fungi, bacteria, nematodes, and fluctuating moisture levels, so another large set of genes goes on the defense against these pathogens (Chen et al. 2015). The shells also become very tough with thick-walled cells and fibers that support the network of veins bulging at the surface of the shell (Halliburton et al. 1975).

So to recap, those peanut shells have to be tough enough to withstand intense physical challenges yet adept enough to adjust to subtle environmental cues. Sitting low in the dirt all that time has roughed up their epidermis and left them pretty well skinned. Sounds like a catcher to me.

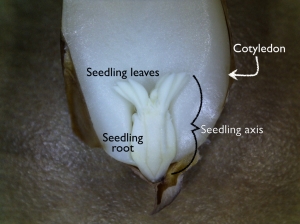

Before you eat those edible seeds, take a closer look at them. The reddish brown papery layer surrounding a peanut seed is its seed coat. Just like other familiar bean seeds, the peanut has two distinct halves which are its cotyledons (“seed leaves”). The cotyledons store a lot of nutrients to support a developing seedling, a role that makes them dense sources of protein and fat calories. Because many legume species use symbiotic bacteria to fix nitrogen from the air, they can afford to pack their seeds full of nitrogen-rich protein.

Looking down at a peanut seed, slightly ajar. The tuft in the center is a set of new leaves that will emerge when the seedling germinates.

Between the cotyledons is a fascinating little structure that looks like a pale feathery mustache. That tiny tuft is the first set of leaves that appears above ground when you plant a fresh peanut.

But of course peanuts plant themselves, as described above. If you occasionally question a baseball manager’s strategy, just think about this insane move. When a flowering peanut pushes its fruits into the soil, the fruits remain tethered to the plant, and the seeds inside do not go far. They basically sit right under the parent plant, waiting for it to die, crowded by dozens and dozens of sibling seeds. Yes, it is a good spot, since those inbred seeds are genetically similar to their parents and would thrive where they did. Still, only a handful of them (at most) can occupy the family spot the following year. For a seed, that’s worse odds than a suicide squeeze. By contrast, most other plant species invest energy and cunning into dispersing their fruits and seeds as far as possible. They explode, or stick, or float, or travel through a gut. Bye bye baby. Peanuts’ odd reproductive habit is called “active geocarpy.” This strategy is rare in plants, but it seems to be associated with unstable soils, often at high altitudes, that are prone to freeze-thaw or extreme wet-dry cycles (Barker, 2005). Maybe active self-planting protects seeds from being buried too deeply or being unearthed when the ground shifts. Maybe sometimes they do roll away but stay in fair territory and colonize new ground.

In the US, we associate peanuts with the American South, and that’s where they are grown now. Although lots of American baseball players come from peanut country – San Francisco catcher Gerald “Buster” Posey grew up in Leesburg, not far from the famous peanut farms of Plains, GA – no major league baseball players have come from the original home of peanuts in southern Bolivia. Recent genetic work has narrowed the most likely origin of our cultivated peanuts (Arachis hypogaea) to a very small region in southern Bolivia, not far from where the borders of Bolivia, Paraguay, and Argentina come together (Bertioli et al. 2016). Peanut cultivation in that region began very early – almost as soon as people got there – and seems to have spread quickly. The Bertioli study estimates that our cultivated peanuts arose as a hybrid between two other groundnut species over 9 thousand years ago, and there is evidence of peanut cultivation in Peru not long after that, about 7800 years ago.

These days the US grows a lot of peanuts, and now we have a major goober glut that even baseball fans can’t soak up. The latest Farm Bill and other agricultural policies encouraged farmers to produce more peanuts and less cotton. We can’t eat all those peanuts, and we can’t store them all either. But peanuts are nutritional powerhouses, so an obvious solution is to give them away, and the USDA has made a deal to ship 500 metric tons of peanuts to Haiti. The heartbreaking part, as reported by the Washington Post and NPR, is that Haitian farmers have been growing peanuts themselves as part of that country’s agricultural recovery. Sending our peanuts to Haiti could undercut their efforts. (UPDATE: Sixty-one advocacy groups have submitted a letter opposing the peanut shipment plan. You can read their arguments here.) Meanwhile, here at home, conditions continue to favor peanut production in spite of the oversupply.

Perhaps the most prominent promotor of peanut production was George Washington Carver, the long-time faculty chair of the Agriculture Department at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. He saw peanuts as a crop that could replace cotton and actually start to heal some of the damage cotton had brought to both soil and souls in the South. As part of his effort, Carver published a booklet of 105 peanut recipes, including both savory and sweet preparations, and yet he somehow failed to mention peanut brittle or boiled peanuts.

Now, if you live in the south you can easily buy canned (meh) or roadside (mmm) boiled peanuts. But if you want something really good, here’s my pitch for making your own boiled peanuts.

Boiled Peanuts

Peanuts must be raw and still in the shell. They may be dried (not roasted) or they may still be damp and soft (“green”). With dried peanuts, it speeds cooking to soak them overnight in water to soften them a bit.

For every pound of peanuts, use a half-gallon of water and about 1/2 cup of salt. Put everything in a pot and bring it to a boil. Continue to boil until the peanut seeds are soft, with no residual crunch to them. Green peanuts will take up to two hours while dried peanuts may take 10 or 12 hours. Be sure to keep the water level high enough to keep all of the shells surrounded by water. Allow the peanuts to cool in the brine and then refrigerate them and eat them within a week.

Be sure to save a few to germinate, like I did. (It’s a video. Click it!):

References

Barker, N. P. (2005). A review and survey of basicarpy, geocarpy, and amphicarpy in the African and Madagascan flora. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, 445-462.

Bertioli, D. J., Cannon, S. B., Froenicke, L., Huang, G., Farmer, A. D., Cannon, E. K., … & Ren, L. (2016). The genome sequences of Arachis duranensis and Arachis ipaensis, the diploid ancestors of cultivated peanut. Nature genetics. http://www.nature.com/ng/journal/v48/n4/full/ng.3517.html

Carver, G.W. (1925) How to Grow the Peanut and 105 Ways of Preparing it for Human Consumption. Tuskegee Institute Press, Bulletin no. 31 (revised from original 1918) http://aggie-horticulture.tamu.edu/fruit-nut/carver-peanut/

Chen X., Yang Q., Li H., Li H., Hong Y., Pan L., Chen N., Zhu F., Chi X., Zhu W., Chen M., Liu H., Yang Z., Zhang E., Wang T., Zhong N., Wang M., Liu H., Wen S., Li X., Zhou G., Li S., Wu H., Varshney R., Liang X. and Yu S. (2015) Transcriptome-wide sequencing provides insights into geocarpy in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Plant Biotechnol. J., doi: 10.1111/pbi.12487

Leuck, D. B., & Hammons, R. O. (1965). Pollen-collecting activities of bees among peanut flowers. Journal of Economic Entomology, 58(5), 1028-1030. http://jee.oxfordjournals.org/content/jee/58/5/1028.full.pdf

Halliburton, B. W., Glasser, W. G., & Byrne, J. M. (1975). An anatomical study of the pericarp of Arachis hypogaea, with special emphasis on the sclereid component. Botanical Gazette, 219-223.

Smith, B. W. (1950). Arachis hypogaea. Aerial flower and subterranean fruit. American Journal of Botany, 802-815.

This is a wonderful and informative piece on peanuts. But I must share my own experience with “bawld goobers”. I have a dedicated group of fans of my boiled peanuts who will attest to the fact that dried peanuts cooked according to your recipe but for only about 4 or 5 hours have a delightful soft crunch as opposed to being like mashed potatoes in a shell when cooked for 8 hrs. After about 4.5 hours at a low simmer, I turn them off and let them sit in the water overnight before draining and serving. Hard to at just one!

LikeLike

Well I defer to you on this one! The ones I get in California are green, and they take about 2 hours. Some online recipes caution that dried peanuts may take a very long time, so perhaps there’s a lot of variation with a long tail. I agree with you whole-heartedly that the super mushy ones are not so great.

LikeLike

We only get green peanuts for a short time in the fall. One well known Southern cookbook says to boil peanuts for 45 min. It took me a while to realize that she was talking about green peanuts not raw peanuts. The good news for me is that the raw ones are available year round and I like them better than green ones.

LikeLike

Father Knows Best

LikeLike

Wow. I write about plants everyday, but this piece on peanuts takes the cake. I had no idea they were so amazing! I don’t think they would grow very well in our heavy clay, but I may have to try it anyway!

LikeLike

Pingback: Closing out the International Year of Pulses with Wishes for Whirled Peas (and a tour of edible legume diversity) | The Botanist in the Kitchen