Regular readers may have noticed that I (Katherine) sometimes go on a rant the week before Thanksgiving. This tradition is probably nothing more than a small annual outburst of snarky impatience that has accumulated over a long academic quarter, but I prefer to pretend that I am clearing space in my heart for gratitude. In past years I’ve gotten worked up about cooked celery, green bean casserole, and, most righteously, pecan pie. This year, my target is pickled peaches.

Anyone unfamiliar with pickled peaches should immediately banish the nasty idea that they are salty or puckered. No, they are the sweet-and-sour kind of pickles. Peaches are slipped free of their fuzzy skins and simmered whole in a heavily spiced vinegar and sugar syrup that preserves them until the winter holidays. Their flesh takes on an amber hue, and arranged on a cut glass serving dish they glisten like old fashioned gold ornaments. Sometimes whole cloves float in the syrup that pools around them. They are sweet, of course, but also tart enough to balance the bulk of a heavy holiday meal.

We fans of pickled peaches wait all year for them, but even after the dish has been passed all around the table, and everyone’s plate is adorned with a golden orb, satisfaction can still slip away. That’s because it is impossible to make a clean stab at a pickled peach and hold it while carving away the first slice of flesh. It is necessary to chase the peach around the plate until it meets an obstacle firm enough to resist it. An obvious counter move would be to give each peach its own place of honor in an antique crystal footed sorbet cup, set at each person’s place. But this elegant solution fails at the first unsuccessful jab with a fork, as the dish’s height and sloped sides give the peach extra loft in its flight towards the centerpiece.

Eventually, a peach will be caught and sliced into, and after that it more or less stays put. The next challenge is to carve the flesh away from the stubborn pit – necessary only because pickled peaches are always of the cling variety, never freestone. That casual observation led me to my first incorrect hypothesis about pickled peaches.

I actually had three hypotheses, all incorrect. The first was that freestone peaches would not stand up to pickling because they are genetically constrained to have what is called melting flesh. The second was that pickled peaches are made from end-of-season cast-offs that didn’t quite live up to fresh peach standards. The third was that, lacking cranberries, southern cooks invented pickled peaches to play the same role on southern plates that cranberry sauce plays in the north.

That last hypothesis is the easiest to dismiss, so I’ll address it first. My idea was that every Thanksgiving table needs a sweet-sour fruit on the side to cut through the richness of the meal, but that peaches, being long out of season, would not be an obvious choice. Moreover, they are not naturally sour and astringent like cranberries are, so they need to be infused with vinegar if they are cleanse a palate. Why wouldn’t a southern cook look to quinces, which ripen in fall and are so tart and tannic that they must be cooked in sugar anyhow? Perhaps, I thought, one year an overly abundant peach harvest spurred the invention of pickled peaches. After that, the recipe must have spread regionally, but only where cranberries were hard to find.

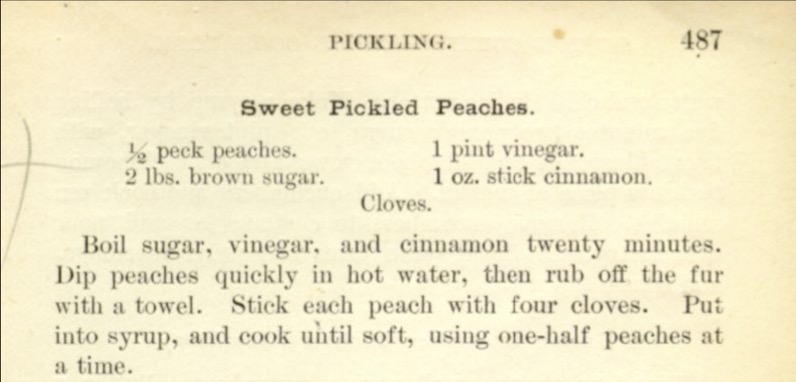

Well, it may be true that cranberries do not grow in the south (although quinces do), but it is not true that pickled peaches were originally restricted to that region and replaced by cranberries in the northeast. The original 1896 edition of Fannie Farmer’s Boston Cooking School Cook Book has a recipe for pickled peaches on page 487 even though, just a few pages later, one could find recipes for cranberry sauce and cranberry jelly. Thus, as far north as New England, where cranberries were abundant, Fannie Farmer was teaching people to boil their peaches in sweet spiced vinegar syrup.

As for my second hypothesis, I was also wrong that pickled peaches are made at the end of the season as a way to use imperfect or unsold fruit. The friendly people at the legendary Dickey Farms in Musella, Georgia, graciously told me which varieties they use for their pickled peaches, and all are varieties that ripen in the first half of peach season. Indeed, three of the four are among the earliest to ripen, according to the University of Georgia . Pickled peaches are not a clever use of unwanted peaches. Peach picklers plan for Thanksgiving six months ahead.

All along my first hypothesis – that it was genetically impossible for pickled peaches to have free pits – seemed most plausible. My logic took two steps. First, most peach varieties grown for canning have what is called “non-melting flesh,” whereas peaches grown for eating fresh usually “melt” as they ripen and become luscious and soft. The firmer non-melting varieties have lost a gene that codes for an enzyme (endopolygalacturonase) that would normally soften cell walls (Gu et al. 2016). Now, the main reason that pickled peaches elude us on the plate is that they remain fairly firm, even though they have been heated in vinegar and canned. Since ordinary commercially canned peaches have non-melting flesh, I assumed that growers and processors would prefer non-melting varieties for their pickled peaches as well.

Second, non-melting varieties never have free pits. It turns out that freestone peaches carry a duplicated copy of the flesh-melting gene that operates close to their pits and allows them to separate cleanly from the rest of the fruit. That second gene also softens up the rest of the peach just a bit, so that it is simply not possible to have a firm-fleshed but freestone fruit. (See this earlier post for details). So while it would be lovely not to have to fight with a pit on Thanksgiving day, I could see that the need for a firmer fruit was probably more important.

Once again, I was wrong. At least two of the four varieties that Dickey Farms processes into pickled peaches are melting flesh types, so clinging stones are not simply an unavoidable byproduct. Melting flesh peaches can be either cling or freestone, yet all of the pickled peaches have difficult pits. I could not find information about the flesh type of a third variety, and the fourth variety (Spring Prince) is indeed non-melting. Obviously, other pickled peach processors may use different varieties, including non-melting types, but in all my years of eating pickled peaches, I have never once encountered one with a free pit.

Reasonable people might wonder why peaches have to be pickled whole. Wouldn’t slicing the peaches before pickling them eliminate both the sliding and the pit fighting? Of course. But then it wouldn’t be Thanksgiving, would it?

References

Chen, C., Guo, J., Cao, K., Zhu, G., Fang, W., Wang, X., … & Wang, L. (2021). Identification of candidate genes associated with slow-melting flesh trait in peach using bulked segregant analysis and RNA-seq. Scientia Horticulturae, 286, 110208.

Farmer, Fannie Merritt (1896) Boston cooking-school cook book. (https://d.lib.msu.edu/fa/3062)

Gu, C., Wang, L., Wang, W., Zhou, H., Ma, B., Zheng, H., … & Han, Y. (2016). Copy number variation of a gene cluster encoding endopolygalacturonase mediates flesh texture and stone adhesion in peach. Journal of experimental botany, 67(6), 1993-2005. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erw021

Serra, O., Giné-Bordonaba, J., Eduardo, I., Bonany, J., Echeverria, G., Larrigaudière, C., & Arús, P. (2017). Genetic analysis of the slow-melting flesh character in peach. Tree Genetics & Genomes, 13(4), 77.

Fascinating. I’m thrilled to learn so much about peaches! I never noticed the softness of the freestone peaches, as I have always preferred them to their counterparts. The only question left unanswered is… why are we learning this a “eating the pickled peaches” time, rather than at “making the pickled peaches” time?

LikeLike

Thanks, Jolene. Yeah, I’m sorry that this comes a bit too late to do anything about it. Last year I was not planning ahead for a covid-restricted holiday, and I ended up using dried peach halves. They were remarkably good, just not the same dish. I stewed them in apple cider vinegar, sugar, and Chinese 5 spice. Just made up the syrup by taste, so I don’t remember the proportions. Depending on where you live, though, you might be able to find some real pickled peaches in the grocery store.

LikeLike

Precious Katherine . . . I woke up two nights before Thanksgiving to find your piece on pickled peaches in my in box—how lovely! We are missing you at our table this year, me particularly as you and I are usually the only stalwarts attempting to chase the refractory fruit across our dinner plates. It particulary warmed my heart since—ALAS!—we were away from home during most of peach season and do not have—sob—a single picked peach in the cupboard to balance Thursday’s rich repast. Reading about them helps fill the void . . . thank you!

>

LikeLike

Tragedy! And I thought that for sure, there would be a place you could get them on your way to the beach, and there would be, but they are sold out! https://www.charlestonspecialtyfoods.com/products/miss-ezzies-carolina-spiced-peaches?_pos=12&_sid=a2885f2c4&_ss=r Maybe Publix?

LikeLike