This is our first of two contributions to Advent Botany 2015.

Sugar plums dance, sugar cookies disappear from Santa’s plate, and candied fruit cake gets passed around and around. Crystals of sugar twinkle in the Christmas lights, like scintillas of sunshine on the darkest day of the year. Katherine and Jeanne explore the many plant sources of sugar.

Even at a chemical level, there is something magical and awe-inspiring about sugar. Plants – those silent, gentle creatures – have the power to harness air and water and the fleeting light energy of a giant fireball 93 million miles away to forge sugar, among the most versatile compounds on earth, and a fuel used by essentially all living organisms.

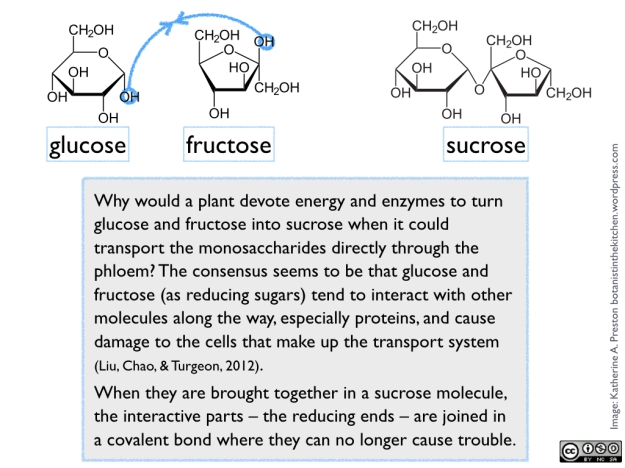

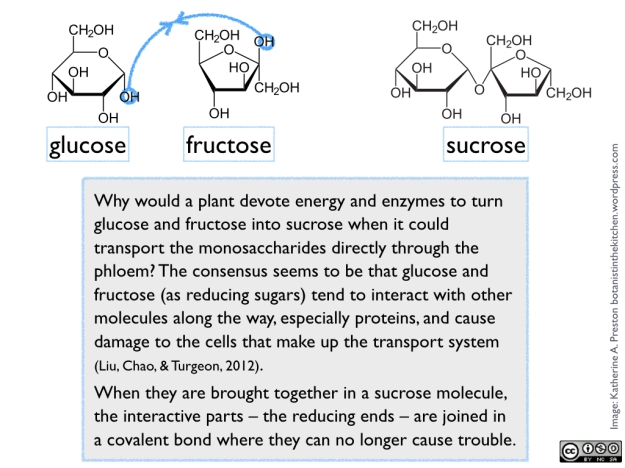

Sugar naturally occurs in various chemical forms, all arising from fundamental 3-carbon components made inside the cells of green photosynthetic tissue. In plant cells, these components are exported from the chloroplasts into the cytoplasm, where they are exposed to a series of enzymes that remodel them into versions of glucose and fructose (both 6-carbon monosaccharides). One molecule of glucose and one of fructose are then joined to form sucrose (a 12-carbon disaccharide). See figure 1.

Figure 1.

Sucrose is what we generally use as table sugar, and it is the form of sugar that a plant loads into its veins and transports throughout its body to be stored or used by growing tissues. When the sucrose reaches other organs, it may be broken back down into glucose and fructose, converted to other sugars, or combined into larger storage or structural molecules, depending on its use in that particular plant part and species. Since we extract sugar from various parts and species, the kind of sugar we harvest from a plant, and how much processing is required, obviously reflects the plant’s own use of the sugar. Continue reading →