Katherine’s search for delicious white chocolate (it exists) leads to a holiday twist on truffles. And whatever your festivities proclivities may be, we Botanists in the Kitchen wish you a very merry Hibiscus and a happy Gomphothere!

White chocolate

’Tis the season to sound the trumpets and pronounce judgment upon the holy or evil nature of traditional holiday foods. Try mentioning fruit cake or egg nog in mixed company and see what happens. If you are among this season’s many vociferous critics of recently trendy white chocolate, you’ve probably been complaining that white “chocolate” is not even chocolate (uncontroversial) and that it tastes like overly sweet vanilla-flavored gummy paste dominated by an odd powdered-milk flavor, and that it exists only to cover over pretzels or perfectly good dark chocolate or to glue peppermint flakes to candy. You might even jump on the white chocolate hot cocoa trend, which has become a social media flash point now that pumpkin spice season is finally over.

It’s true that white chocolate is not technically chocolate; it lacks the cocoa solids that give genuine chocolate its rich complex flavor borne of hundreds of aromatic compounds balanced by just a touch of sour and bitter. However, proper white chocolate is made from cocoa butter, the purified fat component of the Theobroma cacao seeds from which true dark chocolate is also made. Raw cocoa butter has its own subtle scent and creamy texture, and I thought I could use it to make a version of white chocolate more to my liking, with less sugar and no stale milk flavor.

It turns out that working with cocoa butter is tricky, but it gave me the chance to learn a lot more about the nature of this finicky fat. It also turns out that sugar and some kind of milk powder are essential ingredients in all the homemade white chocolate recipes I found, because they seem to make the fat easier to work with. My plan was to make white truffles, which would showcase homemade white chocolate as an ingredient but allow me to balance its unavoidable sweetness with another flavor.

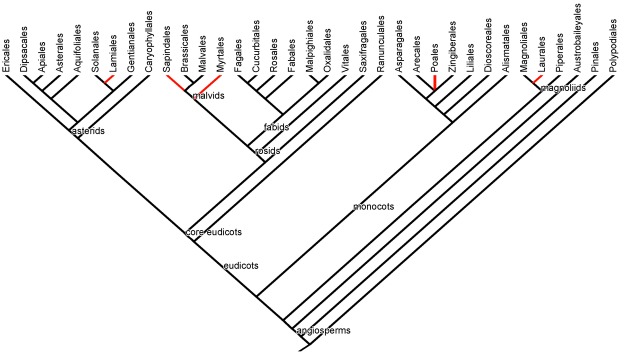

Because it can be fun and instructive to find a culinary match within the same botanical family, I searched for a balancing flavor from the list of common edible members of the Malvaceae. Baobab? Too hard to find locally. Durian? Too risky. Linden tea? Too subtle. Okra? No. Just no. Hibiscus? Bright red and tangy and perfect. Although hibiscus and Theobroma are rarely united in cooking – and they took divergent evolutionary paths about 90 million years ago – I found that these plants work extremely well together. Unlike traditional dark rich chocolate truffles, white cocoa truffles rolled in crimson hibiscus powder melt in your mouth like cool and fluffy snowballs, followed by a refreshing sour kick. Instead of being just one more rich December indulgence, these play up the bright white clear and cold elements of the season. Even better, the most widely available culinary hibiscus flowers come from the African species Hibiscus sabdariffa, sometimes called roselle, which has its own connection to the winter holidays: it stars as the main ingredient in a spicy punch served at Christmastime in the Caribbean.

Cocoa butter

Melting and molding dark chocolate into candies is notoriously difficult because the chocolate can lose its temper and become grainy or develop white oily streaks as it cools. The trouble lies in the cocoa butter, and like many chocolate dilettantes, I became interested in cocoa butter behavior when I tried to learn how to keep my dark chocolate in temper.

Cocoa butter is the fat that Theobroma cacao stores in its seeds to fuel the growth of its seedlings. Like many of the large edible seeds we casually call nuts, cacao seeds are about half fat by weight, but their fat composition is very different from the fat found in almonds, walnuts, or even the ecologically similar Brazil nuts (Chunhieng et al., 2008). In plants and animals, all naturally occurring fat is composed almost entirely of triglycerides, which are based on a glycerol backbone with three fatty acid tails. Those fatty acids can be long or short, and straight (saturated) or kinked (unsaturated). The nature of the tails determines how the individual triglyceride molecules interact to form crystals and whether the fat will be liquid or soft or firm at room temperature (Thomas et al., 2000). Very generally, the more straight tails there are, the more closely and stably the triglyceride molecules can be packed together, and the firmer the fat will be. (Manning and Dimick have a clear description of this in the case of cocoa butter, and their paper is available open source).

Whereas milk fat includes about 400 different kinds of fatty acids (Metin & Hartel, 2012), cocoa butter is dominated by only three (Griffiths & Harwood, 1991). That simple chemical profile isn’t unusual for seeds, but the types and proportions are. Cocoa butter triglycerides mostly contain two long, straight fatty acids (palmitic and stearic) and one long kinked one (oleic), in fairly equal proportions (Griffiths & Harwood, 1991). The high percentage of stearic acid is especially unusual and contributes to the solid state of cocoa butter at room temperature, while the equal combination of these three particular fatty acids causes cocoa butter to melt quickly on our skin or in our mouth.

Another unusual property of cocoa butter is that it actually cools your mouth when it melts. A piece of chocolate on your tongue gradually warms, and at first you feel it approaching your body temperature. However, precisely at its melting point – just below body temperature – it abruptly stops getting warmer, even as it continues to remove heat from your mouth, thereby cooling it. This pause in warming is due to the high latent heat of fusion of the triglyceride molecules. Because it happens just below body temperature, you feel a cooling sensation.

Interestingly, the exact proportions of the three fatty acids varies slightly with genotype and environmental conditions during the growing season (Mustiga et al., 2019). Cocoa butter is, ultimately, food for cacao tree seedlings, and so the precise fatty acid composition of the seeds certainly reflects the species’ seed ecology. To my knowledge, the details have not yet been investigated, but I assume that the fat properties influence both seed longevity under hot tropical temperatures and the ability of seedlings to metabolize the fats as they draw on them for energy during germination. In any case, because the exact proportions of the three fatty acids determines the melting point of cocoa butter, its source and genotype will also affect its behavior in our kitchens or in a factory.

A miniature sleigh and one giant Gomphothere

Speaking of ecology, all that lovely fat and protein and carbohydrate in a cacao seed is great for humans and our chocolate habits, but it doesn’t help T. cacao as a species if at least some of their seeds don’t eventually become trees. Actually, our chocolate habits over the last few millennia have done a lot to spread cacao seeds (Zarrillo et al., 2018), but for the millions of years that cacao existed before humans spread into neotropical cacao territory, other animals must have carried away the cocoa pods.

Given the hefty size of a cacao fruit (about a pound, or 500 grams), its relatively large seeds, and its yellow-orange color, the species appears adapted for dispersal by a correspondingly large animal. But no such animal candidates coexist now with Theobroma cacao or with several other similar neotropical tree species. One long-standing hypothesis has been that tropical fruits with this suite of traits are anachronisms that coevolved with now-extinct megafauna, such as gomphotheres – relatives of American mastodons – or giant ground sloths (Guimarães et al., 2008). At least one genus of gomphothere did co-occur with cacao (Lucas et al. 2013), so it is possible that they spread the seeds, but we need more complete information about their diets to be sure.

We wish you a red hibiscus and a happy gomphothere

Merry Hibiscus

The genus I chose to balance white cocoa’s sweetness and add a bit of festive color was Hibiscus, which includes hundreds of species, but Hibiscus sabdariffa is the one used most often in herbal infusions or as natural coloring or flavor. Because of its global popularity its flowers can sometimes be bought dried and in bulk at co-ops or international markets. The petals are relatively short and so a whorl of fleshy sepals makes up most of the flower, as is obvious after they have been plumped back up by a soak in hot water.

To make the hibiscus powder truffle coating, it is necessary to grind dried flowers to the finest possible powder and sieve out any remaining gritty pieces. I pulverized about half a dozen flowers in a retired coffee grinder, but you can use a mini food processor or a spice grinder. I quickly learned to let the powder settle before opening the grinder, to avoid getting a Gomphothere-sized dose of astringent dust in my human-sized nose.

After grinding, the powder must be sifted through the finest sieve you can manage. I use a gold filter like those designed to filter coffee. It takes time and patience but this step is important for the look and the mouthfeel of the truffles. The sieve full of leftover grit makes a nice cup of tangy tea.

Dried (bottom) and reconstituted calyces (ring of sepals) of Hibiscus sabdariffa, sometimes called roselle

Truffles

Traditional dark chocolate truffles are pretty simple to make: Simmer some cream and let it cool to the point where you might consider taking a very hot bath in it. Herbs or spices may be steeped in the cream during the simmer. Measure the volume of the hot cream in ounces and add twice as many ounces by weight of finely chopped chocolate. Stir gently to melt all the pieces and then allow the mixture (called ganache) to cool at room temperature. Overheating the chocolate initially or cooling the ganache too fast takes the chocolate out of temper. When the ganache is firm, roll it into lumpy balls, coat with cocoa powder, lick your fingers, et voilà.

It turns out that dark chocolate is much more forgiving than pure cocoa butter when it comes to truffles. The first time I tried to make white cocoa truffles, I followed my usual recipe, using chopped cocoa butter in place of dark chocolate and adding some sugar with the cream. Although I was extremely careful not to overheat the cocoa butter, my ganache separated anyway. Whereas dark chocolate contains cocoa solids that support the desired type of crystal formation in solidifying chocolate (Svanberg et al., 2011), cocoa butter does not. In my various experiments with the gentle melting of cocoa butter, I went so far as to sit for an hour on a plastic bag full of grated cocoa butter. Although it should have melted at body temperature, it never got quite soft enough. I finally got the texture right when I accepted a century of professional wisdom and introduced the dreaded milk powder as well as a lot of sugar into the recipe.

Cocoa truffles in hibiscus powder

Below is my current working recipe, subject to additional experimentation:

- 3 oz food grade pure cocoa butter, chopped

- 1/2 cup powdered sugar

- 1 1/2 teaspoons powdered milk

- 1/4 cup cream

- 1/4 cup sugar

- hibiscus powder from 5 or 6 dried hibiscus flowers

In a small food processor, pulverize the cocoa butter, powdered sugar, and powdered milk. The result should be coarse dry crumbs. Place the crumbs in a small heatproof bowl or the top of a double boiler.

Bring the cream to a simmer and dissolve the sugar in it. (For one version I steeped a couple of hibiscus flowers in the cream, which tasted good but made the truffles pink all the way through. Extra cream was needed to account for some of it clinging to the flowers.)

When the cream is the temperature of a hot bath, pour it into the cocoa butter mixture. Remember, cocoa butter melts below body temperature so the cream doesn’t have to be very hot. The crumbs will cool the cream as you stir, and you want the mixture to be just above body temperature as the centers of the crumbs are melting. Those last bits to melt will seed the mixture with the desired type of crystals and favor their formation as the mixture cools.

It will take several hours for the mixture to be firm enough to roll into balls. I usually leave it at room temperature overnight. Do not rush the process by chilling it! Fast cooling favors unstable crystals and your truffles will be grainy.

Roll the mixture into balls and roll them in the hibiscus powder.

Note that you can buy white “chocolate” chips and use them in place of dark chocolate in the usual truffle recipe described above. I tried this and it worked when I increased the chips-to-cream ratio to slightly above 2-to-1. However, do read the ingredient list because many white chocolate chips (especially those labeled “white morsels”) contain no cocoa butter at all. The Gomphotheres would not approve.

White cocoa truffles with hibiscus dust and whole dried hibiscus flowers

References and further reading

Chunhieng, T., Hafidi, A., Pioch, D., Brochier, J., & Didier, M. (2008). Detailed study of Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa) oil micro-compounds: phospholipids, tocopherols and sterols. Journal of the Brazilian Chemical Society, 19(7), 1374-1380.

Gouveia, J. R., de Lira Lixandrão, K. C., Tavares, L. B., Fernando, L., Henrique, P., Garcia, G. E. S., & dos Santos, D. J. (2019). Thermal Transitions of Cocoa Butter: A Novel Characterization Method by Temperature Modulation. Foods, 8(10), 449.

Griffiths, G., & Harwood, J. L. (1991). The regulation of triacylglycerol biosynthesis in cocoa (Theobroma cacao) L. Planta, 184(2), 279-284.

Guimarães Jr, P. R., Galetti, M., & Jordano, P. (2008). Seed dispersal anachronisms: rethinking the fruits extinct megafauna ate. PloS one, 3(3), e1745.

Hernandez-Gutierrez, R., & Magallon, S. (2019). The timing of Malvales evolution: Incorporating its extensive fossil record to inform about lineage diversification. Molecular phylogenetics and evolution, 140, 106606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2019.106606

Lucas, S. G., Yuan, W., & Min, L. (2013). The palaeobiogeography of South American gomphotheres. Journal of Palaeogeography, 2(1), 19-40.

Manning, D. M. & Dimick, P. S. (1985) “Crystal Morphology of Cocoa Butter,” Food Structure: Vol. 4 : No. 2 , Article 9. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/foodmicrostructure/vol4/iss2/9

McGee, H. (2007). On food and cooking: the science and lore of the kitchen. Simon and Schuster.

Metin, S., & Hartel, R. W. (2012). Milk fat and cocoa butter. In Cocoa butter and related compounds (pp. 365-392). AOCS Press.

Mustiga, G. M., Morrissey, J., Stack, J. C., DuVal, A., Royaert, S., Jansen, J., … & Seguine, E. (2019). Identification of climate and genetic factors that control fat content and fatty acid composition of Theobroma cacao L. beans. Frontiers in plant science, 10, 1159.

Svanberg, L., Ahrné, L., Lorén, N., & Windhab, E. (2011). Effect of sugar, cocoa particles and lecithin on cocoa butter crystallisation in seeded and non-seeded chocolate model systems. Journal of Food Engineering, 104(1), 70-80.

Thomas, A., Matthäus, B., & Fiebig, H. J. (2000). Fats and fatty oils. Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 1-84.

Zarrillo, S., Gaikwad, N., Lanaud, C. et al. (2018) The use and domestication of Theobroma cacao during the mid-Holocene in the upper Amazon. Nat Ecol Evol 2, 1879–1888 doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0697-x

Peach and mint, peach and mint, peach and mint – almost becoming a single word. To quiet the voice in my head I had to make some peach-mint jam. The odd combination turned out to be wonderful, and I’m now ready to submit the recipe to a candid world. As we will see below, it’s not without precedent. Mmmmmmpeachmint jam.

Peach and mint, peach and mint, peach and mint – almost becoming a single word. To quiet the voice in my head I had to make some peach-mint jam. The odd combination turned out to be wonderful, and I’m now ready to submit the recipe to a candid world. As we will see below, it’s not without precedent. Mmmmmmpeachmint jam.