If it smells like onion or garlic, it’s in the genus Allium, and it smells that way because of an ancient arms race. Those alliaceous aromas have a lot of sulfur in them, like their counterparts in the crucifers. You can combine them into a Brimstone Tart, if you can get past the tears.

The alliums

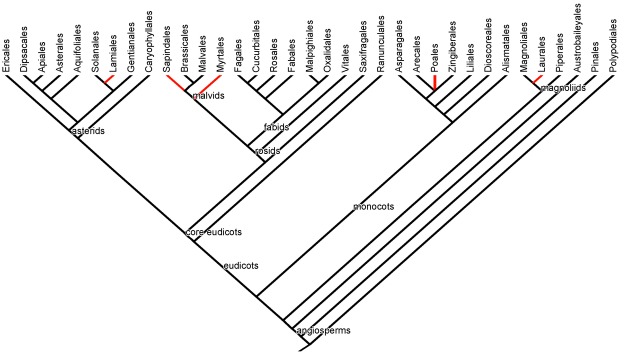

The genus Allium is one of the largest genera on the planet, boasting (probably) over 800 species (Friesen et al. 2006, Hirschegger et al. 2009, Mashayehki and Columbus 2014), with most species clustered around central Asia or western North America. Like all of the very speciose genera, Allium includes tremendous variation and internal evolutionary diversification within the genus, and 15 monophyletic (derived from a single common ancestor) subgenera within Allium are currently recognized (Friesen et al. 2006). Only a few have commonly cultivated (or wildharvested by me) species, however, shown on the phylogeny below. Continue reading