It’s August, and everyone from the American Midwest knows that late summer means fresh sweet corn, and a lot of it. When I was growing up in Indiana, every few days during corn season we would pick up a dozen ears from my family’s favorite roadside stand, just hours after harvest, and cook them right away, before the kernels could start converting their sugar into starch.

Corn season typically peaked the final week of the Indiana State Fair, which always fell between my sister’s birthday and mine. We felt like the whole world was celebrating with us since the Indiana State Fair really is just a giant party, with rides and games and food and music and anatomically impressive hogs. So every year we went to revel in the indulgent atmosphere of the fair alongside thousands of unbridled Hoosiers from all over the state sweating in tank tops and showing off their best pickles. But I most looked forward to the corn. The fair was littered with vendors serving huge ears of fresh-picked local corn straight from a grate set up over a large open flame. As soon as the charred husks were cool enough to peel back into a handle, we sidled up next to our fellow Hoosiers at a trough (literally a trough) of hot melted butter and plunged the roasted ears into it, right up to the hilt. Then we gave them a generous coating of salt from oversized aluminum shakers, passed from hand to greasy hand around the trough and down the line to us. Best birthdays ever.

For this month’s botany lab, I have created a cold summer soup that is as much a celebration of decadent State Fair food as an homage to the millennia of cultivation and adaptation that makes that food possible. The soup features corn four ways, and its various ingredients are available to us only because people have been growing corn (more accurately, maize) and creating distinct varieties for a very long time over an unusually wide geographical area. Maize as a crop goes back to Mesoamerica about 9 thousand years ago, and it had become a substantial part of people’s diets there by about 4500 years ago (Kennet et al. 2020). The spread of maize throughout much of North America was slow because the right mutations had to arise before Native Americans could select for genotypes that were well suited to the local day length, season length, and altitude (Doebley 1990). In the process, people created the varieties we know now, including those in the soup: sugary sweet corn, eaten while immature; dent corn, with soft starchy kernels good for grinding into fine cornmeal, masa, and grits; and flint, with hard round starchy kernels that can be popped or ground into polenta.

The Indiana State Fair and its unabashed celebration of big agriculture most probably sits atop ancient hand-tended corn fields. It is important to recognize that the Fairgrounds occupy land that was traditionally held by the Miami Tribe of Native Americans and lost through a series of coercive treaties in the 19th century. Many members were forced to relocate, but not all, and the Miami Nation of Indiana maintains a cultural presence in the state. The many indigenous tribes throughout the region have a long tradition of agriculture, and as far back as a thousand years ago people would have made corn (Zea mays) the main staple of their diet (Emerson et al. 2020).

Now that corn is big business in the US, dent corn is the most widely grown type because it is used for animal feed, corn oil, high fructose corn syrup, and the many processed foods that have become modern dietary staples. The luckiest dent corn, however, ends up as mash to be fermented into bourbon, which brings me to the name of the soup.

When I was about to turn 13, my mother, who grew up riding, brought a horse into the family. He was a big palomino named Rocky Top, with a mane the color of corn silk and some Tennessee Walker genes that occasionally showed themselves. Naturally, the Osborne Brothers’ song “Rocky Top” was a favorite in our house, especially since my father was, as he described himself, a “tolerable” bluegrass musician who could sometimes be coaxed into singing it.

Corn won’t grow at all on Rocky Top, Dirt’s too rocky by far. That’s why all the folks on Rocky Top Get their corn from a jar

In the song, Rocky Top is an idyl somewhere down in the Tennessee hills. Personally, when I drink corn from a jar, I choose a nice aged bourbon from Kentucky, but that’s beside the point. As long as it’s mostly corn, with just a bit of rye and barley, I’m happy.

This cold late-summer soup features corn four ways, with different flavors and botanical properties that will be obvious as you prepare it. Observation notes are included in the recipe. Like vendors at the Indiana State Fair, this soup plays around in the corners of midwestern and southern food traditions and comes up with something new and delicious. The fresh raw corn base is almost dessert like while croutons of bourbon-soaked grits add intense corn flavor infused with smoke and caramel, and a scattering of buttered popcorn balances the sweet creamy texture of the soup with salty crunch. The soup’s name, of course, honors the inimitable Rocky Top, who was a beloved equine member of our family for over thirty years. The croutons and popcorn might even remind you of rocky outcrops in the Tennessee hills.

Rocky Top soup with corn four ways

Serves 4-6

The preparation is simple, but leave ample time to cook the stock and grits and to chill the ingredients at various stages.

Ingredients

6 large or 8 medium ears of fresh sweet corn in the husk, preferably from a local farm stand or farmers market and as recently picked as possible

1/2 cup of uncooked grits, stone-milled if available, but definitely not “quick”

1/2 cup bourbon (corn in a jar)

1/4 cup unpopped popcorn

Salt (both regular and smoked, if you’ve got it)

Black pepper

White pepper (optional)

1 stick of butter (or olive oil for a vegan version)

Cold soup base

This part of the recipe is quick; my observation notes are long.

1. Before removing the husks, use a large knife to cut the top inch or two from each ear. If insect larvae have gotten into the ears, this is where they will be, and you may prefer not to see them.

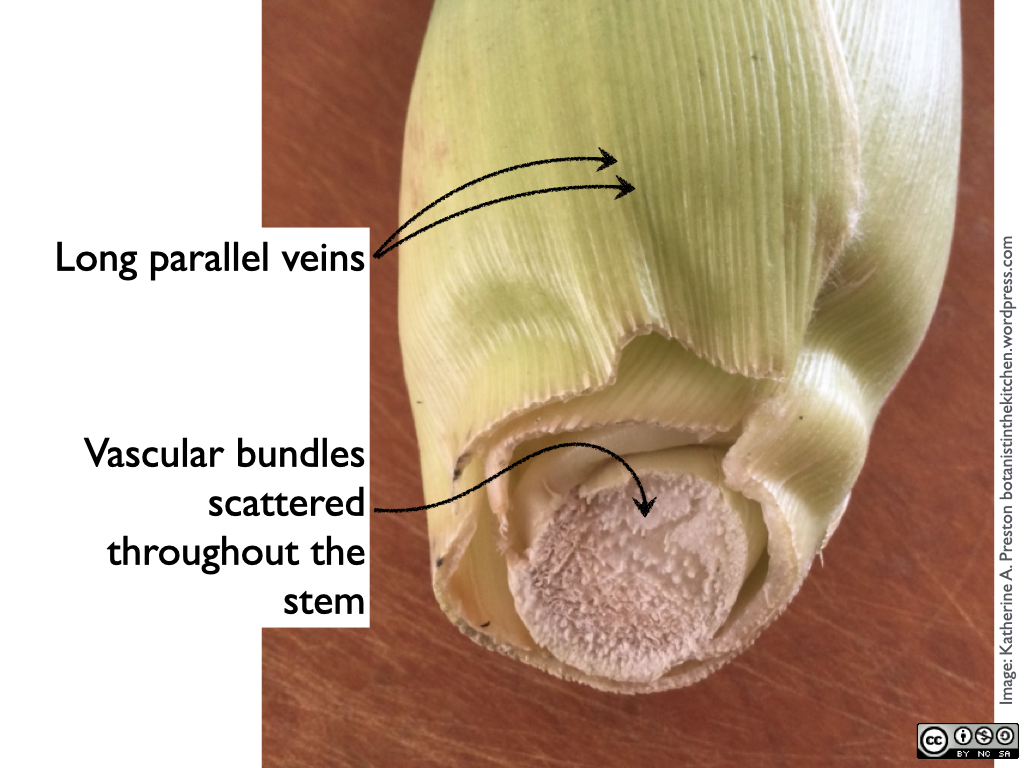

2. Remove the husks, which are leaves enclosing the bud of a giant flowering stalk. Notice their shape and the arrangement of their veins, then take a look at the short bit of stem at the base of the ear to see its scattered vascular bundles. Corn (Zea mays) is typical of monocots in having long narrow leaves with parallel veins and vascular bundles scattered throughout its stems (not in a clear ring). Wash and save the tender inner layer of husks for the stock.

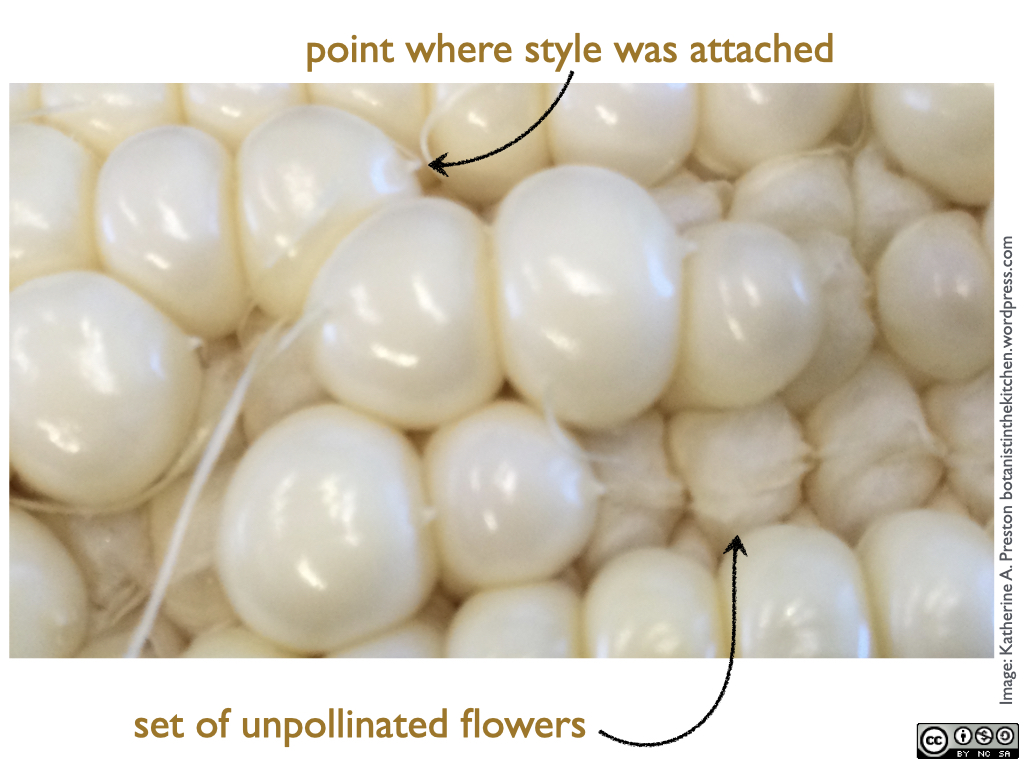

3. Look closely at the corn silk and notice that the strands seem to originate from between the kernels. That is because each one is (or was) attached to the top side (the side facing the tip end) of a single kernel. Amazingly, a strand of silk is the extremely long stigma and style through which germinated pollen grains traveled to fertilize the cells inside what is now a kernel. Sometimes you can see that the silk strand is rough or slightly hairy on one side, the better to capture pollen with. (For more details, see Jeanne’s terrific essay, Super Styled.)

4. Rub the ear under water to remove as much silk as possible. Their race is run, and their job is done.

5. Take a moment to appreciate that each kernel of corn on a cob was once a flower, embedded alongside other flowers in a thick flowering axis. The flowers never had functioning sepals or petals or stamens. (Separate stamen-bearing flowers make the pollen and are found in a tassel on top of the plant). Each flower was essentially a single pistil: an ovary with a style and stigma (those silks!) long enough to protrude beyond the husks where it pollen could find it. The mature product of an ovary is a fruit, so it follows that a kernel of corn is a fruit, not a seed. The fruit functions as a seed, however, because it is essentially just a thin wall fused tightly to the single large seed inside. This type of fruit is called a caryopsis (or, simply, a grain). Fresh corn on the cob is immature, and the fruits are soft, but they would become hard if allowed to mature.

6. Cut the kernels off the cobs and into a bowl. First, cut the cobs in half, then stand them on their cut ends and run a large knife down the sides to remove the kernels. When all kernels have been removed, pull the knife blade across the cobs over the bowl to pull out any residual “milk” (actually endosperm, described below).

7. Notice the very small opaque flattened round structures that pop out of the cut kernels and milked juice. These are embryos. The milky juice is endosperm, the tissue that would supply the embryo with energy and nutrients during germination. At this stage, most of the endosperm is soft and some is still liquid. The liquid portion contains many nuclei because it has not yet been divided into walled cells. Refrigerate the bowl of kernels until the stock has been made and cooled.

8. Look closely at one of the empty cobs. Notice that the sockets that once held kernels are ringed with short papery ruffles. These structures – paleas, lemmas, and glumes– are evidence that the corn cob is much more complicated than it seems. Those empty sockets held not one but two corn flowers, one of which simply never developed. The flower pairs were borne on a very tiny branch with two short glumes at its base. Each flower, in turn, was enclosed by a pair of thin structures, one palea and one lemma. The raggedy ruffles are glumes and paleas and lemmas and are left behind when you eat corn off the cob or shave off the kernels with a knife.

9. Place the cobs and the reserved tender husks into a saucepan, add water to barely cover them, and simmer for about 30 minutes to make a stock. Remove the cobs and husks and allow the stock to cool to room temperature.

10. Move the kernels and milky endosperm from the bowl into a blender and add about 1/4 cup of the stock. Blend very well until the soup is a fine silky purée. Add small amounts of the stock as needed to ease the blending and achieve the consistency you prefer. Salt very sparingly; you want to retain the grassy sweetness of the raw fresh corn. Chill thoroughly.

This soup should be made no more than a day ahead for peak flavor. It is raw and may start to ferment after several days.

Grits croutons

In a pinch, you can use polenta, but the texture will be less interesting and the cuisine will be less American.

1. Place the grits and the bourbon in a heavy-bottomed saucepan, and allow the grits to soak for 30 minutes.

2. Notice that grits, especially traditional stone milled grits, vary much more in particle size than polenta does. Could that be why most people treat “grits” as plural and “polenta” as a singular mass noun? It won’t be obvious, but grits are generally made of dent corn and polenta is made of harder flint corn.

4. Add a tablespoon of butter, a teaspoon of salt, and several grinds of white pepper (about 1/4 teaspoon). If you have smoked salt available, use it here.

3. Cook according to the directions for your particular grits. If you have leftover corn cob stock, use it, supplementing with water if needed.

4. Continue to cook and stir the grits until they are thoroughly done and very thick, like mashed potatoes. You may need to cook longer than directed to get the grits thick enough.

5. Spread the grits into a couple of buttered loaf pans or a square cake pan and chill them for at least an hour, until they are well set. The grits should be about half an inch thick in the pan.

6. Use a table knife to cut the chilled grits into one-inch squares and turn them out into a roasting pan. Toss them with soft butter or olive oil and bake them at 350º for 20 minutes or until crispy on the outside. (It is also possible to fry them in a pan, but they tend to fall apart because they are more fragile than polenta squares.)

7. Croutons should be room temperature or warm but not hot when you serve the soup. You want to keep the soup cool. Croutons may be reheated if needed.

Popcorn topping

1. Notice that popcorn is hard because it has been allowed to mature before harvest, and the once liquid endosperm has been divided into separate cells containing the previously free floating nuclei. Popcorn is a variety of flint corn, so it has a round end without the depressed center seen in dent corn. The nutritive endosperm of popping corn is much starchier than sweet corn would ever get. Although popcorn seems very dry, there is some residual water inside. When heated, that water becomes steam and swells the starch until it bursts the kernel open.

2. Pop the popcorn using your favorite method. Admire the fluffy white expanded endosperm.

2. Butter and salt the popcorn generously, using about 4 tablespoons of melted butter.

Assembling the soup

1. Pour the chilled soup into bowls

2. Scatter several grits croutons over the soup. Most will sink

3. Top generously with popcorn and grind some black pepper over the top

4. Serve immediately to maintain the contrasts in temperature and texture

References and resources

My favorite sources of stone-milled grits are Anson Mills and Nora Mills. Anson Mills also sells popcorn and their website has several interesting pages about the history and botany of the foods they mill.

Doebley, J. (1990). Molecular evidence and the evolution of maize. Economic Botany, 44(3), 6-27.

Doebley, J. F., Goodman, O. M., & Stuber, C. W. (1986). Exceptional genetic divergence of northern flint corn. American Journal of Botany, 73(1), 64-69.

Emerson, T. E., Hedman, K. M., Simon, M. L., Fort, M. A., & Witt, K. E. (2020). Isotopic confirmation of the timing and intensity of maize consumption in greater Cahokia. American Antiquity, 85(2), 241-262.

Kennett, D. J., Prufer, K. M., Culleton, B. J., George, R. J., Robinson, M., Trask, W. R., … & Gutierrez, S. M. (2020). Early isotopic evidence for maize as a staple grain in the Americas. Science Advances, 6(23), eaba3245.

Nickerson, N. H. (1954). Morphological analysis of the maize ear. American Journal of Botany, 87-92.

Weatherwax, P. (1916). Morphology of the flowers of Zea mays. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club, 43(3), 127-144.

I enjoy reading the botanist in the kitchen! Where have you been? Well, I look forward to seeing your articles!

LikeLike

Thanks, Denise! We have slowed down our posting a little bit because we are working on a book, but we do still have some new posts in the pipeline, so stay tuned. And thank you for reading!

LikeLike

wow! I’d like to try this…let me go out and buy some bourbon….

sure love your posts!

LikeLike

You might have to taste a few different bourbons just to be sure you find the perfect one 🙂

For this recipe, I used the ordinary bottle of Makers Mark and not my usual fancy sipping bourbon. Maker’s Mark is good bourbon, don’t get me wrong. But I use it mainly for cooking or making bourbon balls because it’s mellower than some others. Here, that quality suits the croutons well. I would avoid a bottom-shelf bourbon, though, to avoid a harsh taste.

LikeLike

Love your posts! I came looking for info on pineapples ( pineapple ovules, to be exact) and I adore how you bring together the scientific bits and culinary bits! I’m now doing my first year in college after dropping out years ago and I’ve chosen Agricultural Science and I like it more than I expected! Anyway love your works!

LikeLike