Coconut palms grow some of the biggest seeds on the planet (coconuts), and the tiny black specks in very good real vanilla ice cream are clumps of some of the smallest, seeds from the fruit of the vanilla orchid (the vanilla “bean”). Both palms and orchids are in the large clade of plants called monocots. About a sixth of flowering plant species are monocots, and among them are several noteworthy botanical record-holders and important food plants, all subject to biological factors pushing the size of their seeds to the extremes. Continue reading

Author Archives: Jeanne L. D. Osnas

A biologist eating for two

This is a bit tangential to our usual fare, but I think it’s fun, and you may as well. A friend of mine, Cara Bertron, edits the creative and delightful quarterly compendium Pocket Guide. I submitted this image, entitled “A biologist eating for two,” for the current issue, which is themed “secret recipes.” It’s a cladogram of the phylogenetic relationships among all the (multicellular) organisms I (knowingly) ate when I was pregnant with my now two-year-old daughter. Continue reading

Going bananas

What can make me feel less guilty about buying bananas? Science.

I am genuinely curious about the size of the fraction of carbon in my two-year-old that is derived from bananas. When we have bananas in the house, which is most of the time, she eats at least part of one every day. She loves them peeled, in smoothies, dried, in banana bread, or in these banana-rich cookies, which sound like they shouldn’t be good but are totally amazing. Bananas are inexpensive and delicious, and making nutritious food with them gives me a sense of parental accomplishment. Nonetheless, always I feel a niggling sense of guilt whenever I plunk a bunch of bananas into the shopping cart. Prosaic though it may be, most of this is contrition inspired by the “local food” movement. I know that very little is benign about the process responsible for bringing these highly perishable tropical fruits to my table for less than a dollar a pound. The remainder of my remorse is conviction that bananas should not be taken for granted. Not only is banana history and biology interesting, but the banana variety in our grocery stores, the Cavendish, is in danger of commercial extinction. There isn’t an easy solution to the problem or an obvious candidate for a replacement variety. The history of the Cavendish’s rise, and the biology behind its current peril, makes for a good story. Continue reading

Our Easter Bunny is a Botanist

Plant-dyed Easter eggs inspire a glimpse at the diversity of plant pigments.

(scene from Pride and Prejudice of dying ribbons with beets)

Pigments serve a variety of roles in plants. Many pigments have physiological roles within plants and protect plant tissues from sunburn and pathogens and herbivores (see review by Koes et al. 2005). Most noticeably, however, their brilliant colors attract animal pollinators to flowers and seed dispersers to fruit. Humans are also interested in plant pigments, in part because they color and sometimes flavor our food, are potentially medicinally active, and have been used as natural dyes and paints for millennia.

Last weekend I made some natural Easter egg dyes from turmeric and beets (I followed these instructions). We also considered making dyes from red and yellow onion skins or red cabbage, but we kept it simple. This handful of plants used to make cheap, easy, homemade dyes can give us some insight into of the chemical and evolutionary diversity of plant pigments. Continue reading

Hollies, Yerba maté, and the botany of caffeine

Yerba maté, the popular herbal tea from South America, is a species of holly. It’s also caffeinated, a characteristic shared by only a small number of other plants.

Along with conifer trees and mistletoe, hollies are a botanical hallmark of the winter holiday season in Europe and the United States. Most hollies are dense evergreen shrubs or small trees and produce beautiful red fruits that stay on the plant through the cold winter months. Sprays of the dark green foliage grace festive decorations, and wild and cultivated hollies punctuate spare winter landscapes. Especially popular in winter, too, are warm beverages. One of the most popular, at least in South America but increasingly elsewhere, is yerba maté. It is a seasonally appropriate choice because the maté plant is a holly. Unlike the decorative hollies, usually American (Ilex opaca) or English (Ilex aquifolium) holly, maté (Ilex paraguariensis) is caffeinated. This puts it in rare company, not only among hollies, but among all plants. Continue reading

Cranberries, blueberries, and huckleberries, oh my! And lingonberries, billberries…

Flavorful and juicy thought it may be, Thanksgiving turkey, for me, is merely the vehicle for the real star of the meal: cranberry sauce. And cranberry is in the same genus as blueberries, lingonberries, huckleberries, and billberries. And they all make their own pectin. Let us give thanks this holiday season for Vaccinium.

Cranberry sauce is my favorite staple item at our big holiday dinners. Long-prized by indigenous North Americans, cranberries would have been in the diet of those Native Americans participating in the first Thanksgiving if not part of the meal itself. When the fresh cranberries hit the stores in late fall, we stock up. Cranberries, however, are not the only member of their genus that is perennially in our freezers or in our annual diet: blueberries, many huckleberries, lingonberries, and billberries are all in the large genus Vaccinium (family Ericaceae, order Ericales). Continue reading

Nasturtiums and the birds and the bees

Hummingbirds and ancient bees are responsible for the color and shape of nasturtium blossoms and have a unique view of them, explains Jeanne over salad.

Fall frost hasn’t yet claimed our nasturtiums (Tropaeolum majus; Tropaeolaceae family). The large, colorful blooms amidst the round leaves are still spilling over planting boxes. All parts of the plant are edible and boast spicy mustard oil glucosinolates, betraying the plant’s membership in the order Brassicales, along with the cruciferous vegetables and mustard in the Brassicaceae family, capers (Capparaceae), and papaya (Caricaceae; try the seeds, as suggested here). I’ve heard that the immature flower buds and immature seed pods can be pickled like capers, but I haven’t tried it yet. Mostly I use the flowers, throwing a few in a salad or chopping them coarsely with other herbs and stirring them into strained yogurt or butter to put on top of roasted vegetables or lentils. In addition to the mustardy kick, the sweet flower nectar adds to these dishes. Continue reading

Evolution of Lemon Flavor

A batch of lemon balm-lemon verbena syrup reminds Jeanne of the multiple evolutionary origins of lemon flavor.

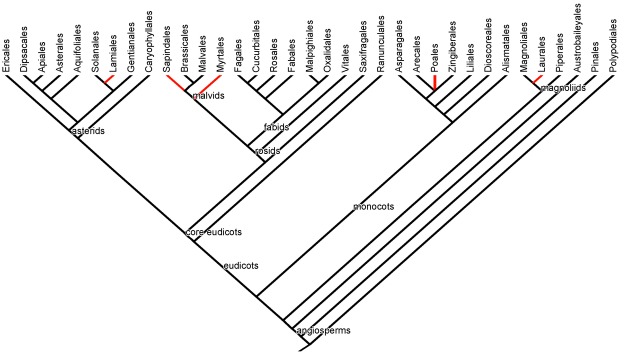

The citrus lemon itself is only one of many plant species that lends its namesake flavor or fragrance to our food and drinks. Lemon flavor primarily comes from a few terpenoid essential oils: citral (also called geranial, neral, or lemonal), linalool, limonene, geraniol, and citronellal. The production of one or more of these essential oils has independently evolved multiple times in species on widely separated branches of the plant phylogeny (see figure).

The citrus lemon itself is only one of many plant species that lends its namesake flavor or fragrance to our food and drinks. Lemon flavor primarily comes from a few terpenoid essential oils: citral (also called geranial, neral, or lemonal), linalool, limonene, geraniol, and citronellal. The production of one or more of these essential oils has independently evolved multiple times in species on widely separated branches of the plant phylogeny (see figure).

Phylogeny of plant taxonomic orders with edibles (click the tree to enlarge). Orders with species with lemony essential oils are highlighted in red. For a refresher on reading this phylogeny, please see our food plant tree of life page.

Super styled

Corn silks are annoying, but they’re also amazing. The longest styles on the planet don’t make it easy for corn pollen to do its job. Gain new respect for your corn on the cob.

Fresh corn (Zea mays, Poeaceae) is a summertime treat. Shucking corn silks, though, can be a pain. Corn silks, however, are amazing, and maybe knowing why will ameliorate their annoyingness. Formally corn silks are the style, the part of the female flower that intercepts pollen. Female flowers of many species have a stigma, a sticky pad, atop their styles to intercept pollen, but corn silks are lined with sticky trichomes (like hairs) that essentially do the same thing. Corn silks are incredibly long styles. Can you think of another plant with a flower appendage that could rival it? I can’t. Continue reading

Tarragon’s family tree

Tarragon is one of many Artemisia species with a storied past. Jeanne introduces you to her favorite genus.

If you love eating French food, and especially if you love cooking it, when you see a tarragon bush, inevitably you think of the French quartet fines herbes: fresh parsley, chives, tarragon and chervil. You may reminisce about a perfect (or broken) Béarnaise sauce. These days when I pass my tarragon plant I vow to actually use it, as we’ve neglected it this year. I also think of sagebrush. And absinthe, martinis, and Shakespeare. And weeds, malaria, and hippies. I attribute this motley mental association to tarragon’s membership in my favorite genus, Artemisia, a large group in the composite (sunflower) family, Asteraceae, with a rich history. Continue reading