What is hairy, green, full of slime, and delicious covered in chocolate? It has to be okra, bhindi, gumbo, Abelmoschus esculentus, the edible parent of musk. Katherine explores okra structure, its kinship with chocolate, and especially its slippery nature. What’s not to like?

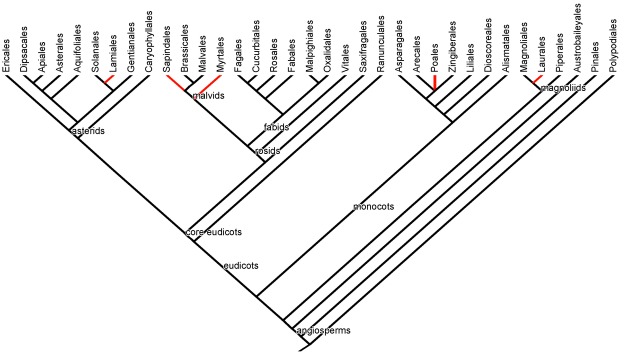

People often ask me about okra slime. Rarely do they ask for a good chocolate and okra recipe, which I will share unbidden. With or without the chocolate, though, okra is a tasty vegetable. The fruits can be fried, pickled, roasted, sautéed, and stewed. Young leaves are also edible, although I have never tried them and have no recipes. Okra fruits are low in calories and glycemic index and high in vitamin C, fiber, and minerals. The plant grows vigorously and quickly in hot climates, producing large and lovely cream colored flowers with red centers and imbricate petals. The bright green or rich burgundy young fruits are covered in soft hairs. When they are sliced raw, they look like intricate lace doilies. In stews, the slices look coarser, like wagon wheels. And yes, okra is slimy. And it is in the mallow family (Malvaceae), along with cotton, hibiscus, durian fruit, and chocolate. Continue reading