Why do so many rich tropical spices come from a few basal branches of the plant evolutionary tree? Katherine looks to their ancestral roots and finds a cake recipe for the mesozoic diet.

I think it was the Basal Angiosperm Cake that established our friendship a decade ago. Jeanne was the only student in my plant taxonomy class to appreciate the phylogeny-based cake I had made to mark the birthday of my co-teacher and colleague, Will Cornwell. Although I am genuinely fond of Will, I confess to using his birthday as an excuse to play around with ingredients derived from the lowermost branches of the flowering plant evolutionary tree. The recipe wasn’t even pure, since I abandoned the phylogenetically apt avocado for a crowd-pleasing evolutionary new-comer, chocolate. It also included flour and sugar, both monocots. As flawed as it was, the cake episode showed that Jeanne and I share some unusual intellectual character states – synapomorphies of the brain – and it launched our botanical collaborations.

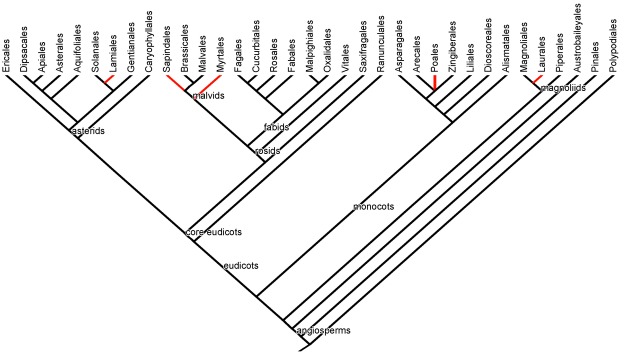

Branches at the base of the angiosperm tree

The basal angiosperms (broadly construed) are the groups that diverged from the rest of the flowering plants (angiosperms) relatively early in their evolution. They give us the highly aromatic spices that inspired my cake – star anise, black pepper, bay leaf, cinnamon, and nutmeg. They also include water lilies and some familiar tree species – magnolias, tulip tree (Liriodendron), bay laurels, avocado, pawpaw (Asimina), and sassafras. Continue reading