Angelica archangelica may be the most festive species in a crowded field of charismatic relatives. Just watch out for the toxic branches of the Apiaceae family tree. This essay is one of our two contributions to this year’s Advent Botany holiday essay collection.

For scientific names of plants associated with the winter holidays, I think it would be hard to beat Angelica archangelica. Commonly known just as angelica or garden angelica, A. archangelica is one of the few cultivated members among the 60-ish species of large biennial herbs in the genus. They are distributed primarily across the northern reaches of Europe, Asia, and western North America.

Angelica stalks candied and photographed by hunter-harvester-gardener Hank Shaw. Recipe on his blog

Candied angelica stalks (young stems and petioles from first-year plants) have long been prized in Western Europe as a unique confection or addition to baked goods. If your path this holiday crosses with a fruitcake studded with bright green chunks, those are unfortunately dyed pieces of candied angelica stalk. Or you may have a qualitatively different experience with angelica in the form of delicious liqueurs that include the root or fruit of the plant as an ingredient. The floral, spicy, and fresh flavor of angelica graces gins, vermouths, absinthes, aquavits, bitters, and Chartreuse, among others (Amy Stewart’s website accompaniment to her book The Drunken Botanist has some tips for growing and using angelica for the DIY mixologist).

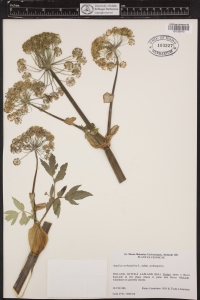

Wild A. archangelica specimen archived at the Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria.

Several other species of angelica besides A. archangelica historically served as locally important medicine or, rarely, food sources. For example, Angelica sinensis is commonly known as “dong quai,” a well-known constituent of traditional Chinese herbal medicine. Some other European species are considered safe to use as food, but in general reports conflict about Angelica edibility, aside from A. archangelica. Complicating matters is the apparent tendency of some possibly nontoxic Angelica species (such as A. lucida in Alaska) to hybridize with Cicuta species, the related and deadly poisonous genus of “water hemlocks” (Schofield, 1992).

Angelica lucida in Nome, Alaska. Photo by M. Carlson. Also note the Artemisia tilesii, a close relative of the mugwort we mentioned in our Artemisia essay.

This hybridization phenomenon is likely helped along by the fact that Angelica’s toxic relatives can be locally numerous and diverse, and the exact relationships involved lack total clarity. Thanks to modern molecular systematics, we now know that the genus is paraphyletic, meaning not all Angelica species share the same most recent common ancestor (Liao et al., 2013). When taxonomists get around to it, some Angelica species, including dong quai, will get new genus names. Other species currently enjoying other genus names may come to discover that they are long-lost Angelica.

That tendency for a deliciously aromatic and edible plant species to be closely related to an insanely toxic thing is a recursive pattern for the entire charismatic plant family to which angelica owes its existence: the Apiaceae. With 3780 species in 434 genera (according to the Missouri Botanical Garden’s Angiosperm Phylogeny Website), the Apiaceae is the 16th largest plant family and is one of the most important from a culinary perspective.

Cultivated root foods from the family include carrots, celery root, parsnips, water parsnip (Sium), and earthnut (Conopodium).

Stem, petiole, and leaf foods, in addition to angelica, include fennel, celery, parsley, dill, cilantro/coriander, lovage, chervil, cicely, and culantro.

Spices from the family mostly come from the small, dry, indehiscent fruits (a fruit type called schizocarps) that are usually just called “seeds.” These include coriander, caraway, ajwain, anise, fennel, and cumin. Asafoetida is the dried resin from the roots of species in the Apiaceae genus Ferula.

Beach lovage. Photo from the Consortia of Pacific Northwest Herbaria.

Wildharvesting guides can help you learn which wild Apiaceae are edible, and some of these are wonderful. This summer I collected beach lovage (Ligusticum scoticum) near Homer, Alaska, which I think was even more delicious than the domesticated lovage (Levisticum officinale) growing in my garden. If you do want to go down this route, however, use extreme caution. Some of the poisonous plants in the family are famous, such as the “hemlock” (Conium maculatum) that killed Socrates, but the rest of the family is generally dangerous. Toxicity in Apiaceae isn’t just restricted to problems associated with eating the plants, either. The sap from many genera are phototoxic, meaning that if you get the sap on your skin in the sun, you will end up with a very nasty chemical burn.

This is a problem for hikers and people pulling weeds. One article from this past summer about Heracleum mantegazzianum had a memorable headline: “Plant expert explains how flesh burning giant hogweed is invading America.”

Recognizing that a plant belongs to the Apiaceae is easy, at least when the inflorescences are available. The family used to be called Umbelliferae in honor of the beautiful umbel-shaped inflorescences typical of its members. Identifying Apiaceae taxa to species, however, can be maddeningly difficult even without contending with hybridization. If you are at all in doubt, don’t eat wild Apiaceae, and cede the field to the toxic relatives.

It’s no wonder that two of the three cornerstone “aromatics” of French cooking—onion, carrot, and celery—are from the Apiaceae. The family boasts a wonderfully diverse set of fragrant compounds. We’ve mentioned some of them previously in our post on isomers. It would be fascinating to explore the evolution of both toxic and aromatic compounds in the family.

In some plants the delicious and poisonous compounds are one and the same. This is probably the case for the monoterpenes in the Apiaceae and the alkaloids in the edible nightshades. At least in the genus Angelica, however, some of the aromatic compounds may function in part as attractants for pollinators (Tollsten, Knudsen, & Bergstrom, 1994).

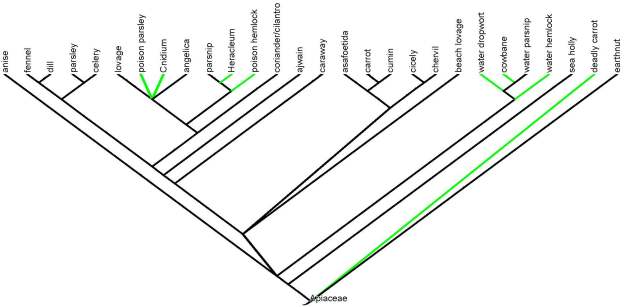

I’ve put together a quick diagram below of the Apiaceae phylogeny showing the positions of some charistmatic members of the family, both edible and poisonous.

Phylogenetic relationships of some edible and toxic species in the Apiaceae. Toxic branches in green. This tree includes numerous polytomies: nodes with more than two descendant clades that likely indicate that there are not enough data to resolve the pattern of evolution. The quantitative systematics of the Apiaceae is clearly in progress. If you need a refresher on reading phylogenetic trees, check out our primer. Tree data from Phylomatic; image constructed using Mesquite.

Speaking of categorizing plants into groups by name, we know Carl Linnaeus as an important 18th-century Swedish naturalist who invented the scientific naming conventions still used today. It was he who coined the name Angelica archangelica, incorporating the prevailing common name of the herb, “archangel,” which originated with a story in the 14th century that the archangel had passed down the medicinal knowledge of the herb to mortal practitioners (Kew Science, 2018).

18th-century Sami boat sleigh, pulled by domestic reindeer. Etching by Knud Leems in 1767, found in Robinson and Kassam.

Linnaeus also dabbled in ethnography. At the age of 25 he traveled to Lapland in 1732 to observe life among the reindeer-herding Sami people (Lindskog, 2017). He was keenly interested in the Sami diet and recorded their use of Angelica archangelica, which is still an important component of the traditional Sami diet and pharmacopeia. The Sami in Linnaeus’s time harvested it in the wild but also probably grew it agriculturally to a limited extent (Rautio, Linkowski, & Östlund, 2016). One application that stood out to Linnaeus was the use of angelica to flavor and preserve the Sami’s reindeer milk.

As a fellow denizen of the far North, it is plausible that Santa’s interest in reindeer extends beyond aerial transportation. To be on the safe side, you may want to put a stick of candied angelica in that milk you’re leaving out alongside the plate of cookies—or maybe fruitcake—on Christmas Eve. Or perhaps at your house Santa would prefer angelica left out in the form of a nice digestif. Here’s hoping for angelica seeds in my stocking.

References (below)

Kew Science. (2018). Angelica archangelica L. | Plants of the World Online | Kew Science. Retrieved December 13, 2018, from http://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:837560-1

Liao, C., Downie, S. R., Li, Q., Yu, Y., He, X., & Zhou, B. (2013). New Insights into the Phylogeny of <I>Angelica</I> and its Allies (Apiaceae) with Emphasis on East Asian Species, Inferred from nrDNA, cpDNA, and Morphological Evidence. Systematic Botany, 38(1), 266–281. doi:10.1600/036364413X662060

Lindskog, A. (2017). Constructing and Classifying ‘the North’: Linnaeus and Lapland. In Romantic Norths (pp. 75–99). Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-51246-4_4

Rautio, A.-M., Linkowski, W. A., & Östlund, L. (2016). “They Followed the Power of the Plant”: Historical Sami Harvest and Traditional Ecological Knowledge (Tek) of Angelica archangelica in Northern Fennoscandia. Journal of Ethnobiology, 36(3), 617–636. doi:10.2993/0278-0771-36.3.617

Robinson, M. P., & Kassam, K.-A. S. (1998). Sami Potatoes: Living with reindeer and Perestroika. Canada: Bayeux Arts Inc.

Schofield, J. J. (1992). Discovering wild plants: Alaska, western Canada, the northwest. Retrieved from https://wizard.unbc.ca/record=b1095552~S3

Tollsten, L., Knudsen, J. T., & Bergstrom, L. G. (1994). Floral scent in generalistic Angelica (Apiaceae) – An adaptive character? Biochemical Systematics and Ecology, 22(2), 161–169. doi:10.1016/0305-1978(94)90006-X